In 2011, progressive activist and author Eli Pariser told an unsettling story about the way that social networks could be skewing our view of the world. "I've always gone out of my way to meet conservatives," he said at a TED Talk. "And so I was surprised when I noticed one day that the conservatives had disappeared from my Facebook feed. And what it turned out was going on was that Facebook was looking at which links I clicked on, and it was noticing that, actually, I was clicking more on my liberal friends' links than on my conservative friends' links. And without consulting me about it, it had edited them out. They disappeared."

Pariser was talking about what he called the "filter bubble," a personalized shield that internet companies create to show us more of what we already like and less of what we don't. There are many manifestations of Pariser's bubble, including targeted ads and search results (which Google, for example, tweaks based on your web history). But Facebook's News Feed algorithm is one of the most obvious and close-cutting; a company is, however benevolently, indirectly choosing whose opinions you get to see. In a study published in Science, however, Facebook argues that it's not your feed that's primarily stopping you from reading opposing viewpoints — it's you.

"People's individual choices ... matter more than any kind of algorithmic choice."

"People's individual choices about who to interact with and what to select matter more than any kind of algorithmic choice," says researcher Eytan Bakshy. Bakshy and his two co-authors are part of Facebook's data science team (one, Lada Adamic, is also an associate professor at the University of Michigan). In their latest research, they used data from millions of Facebook users to look at what determines whether someone sees, clicks, or shares a piece of news that might not mesh with their political ideas.

Bakshy and his team started with aggregated, anonymous statistics from 10.1 million US Facebook users whose profiles listed a political stance. From there, they examined links that were classified as "hard news" (as opposed to entertainment or sports) and sorted them based on political alignment — whether the link had been shared more by people who identified themselves as liberal or conservative. Then, they checked on how frequently those links appeared at various points in the viewing process. Were people's friends sharing ideologically opposing content? Were users actually seeing it? And if they were seeing it, were they clicking?

This work follows up on an earlier finding that while you might interact mostly with a few close friends, the "vast majority" of information comes from weaker ties. At the time, Bakshy said this suggested that "Facebook isn’t the echo chamber that some might expect," since these weak ties were often from different communities — just think of what you see from your relatives and high school friends. But Facebook's News Feed algorithm prioritizes the strong ties, showing you more from people whose posts you've liked, commented on, or shared (among other things) in the past. In theory, this could trap users in an echo chamber full of people they already agree with.

A small number of opposing viewpoints do get shut out of the News Feed

Bakshy says roughly equal numbers of people identify as liberal and conservative on Facebook, but their networks aren't equally liberal and conservative; for users who report their affiliation, an average of 23 percent of friends identify with the opposite side. Conservatives are slightly more likely to share content overall, but overall, the study found that around a quarter of the news shared by liberals' friends was aligned with conservatives, and a third of conservatives' friends' content was liberal. "Liberals tend to have less opportunities to be exposed to content shared from conservatives because they tend to be less connected to individuals who share primarily from conservative sources," says Bakshy.

The test here is whether those shared links actually showed up in users' news feeds — or if Facebook has, in fact, edited them out. As it turns out, Facebook does edit out a portion of them. According to the data, if you're a liberal, a conservative article is 8 percent less likely to make it into your news feed than a liberal one. If you're conservative, you're 5 percent less likely to see liberal news. In absolute terms, both liberals and conservatives see about 1 percent less news from the opposing side than they would if Facebook didn't tweak the news feed.

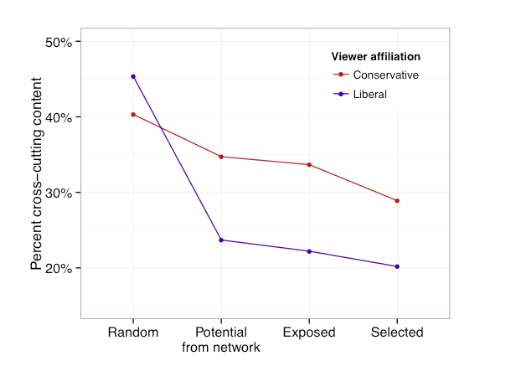

The proportion of opposing links that liberals and conservatives would see if sharing were completely random, compared to what their friends post and what they see or click.

This research, however, found that the drop is bigger between what people see and what they click on. About 23 percent of what liberals' friends share is conservative. Twenty-two percent of what they see in the News Feed is, and the pieces they actually click on are 20 percent conservative. For conservatives, their friends share 34 percent liberal content, they see 33 percent, and they click on 29 percent. (Respectively, that's 6 percent and 17 percent less likely to click than see.) Based on these numbers, the echo chamber we select for is ultimately bigger than the one Facebook picks for us, whether that's because we know fewer people from the other side of the aisle or because we pay less attention to what they share.

Pariser has published his own response to the study on Medium, where he calls the effect of the algorithm "not insignificant," particularly noting that the algorithm is only slightly less important than clickthrough rates for liberals. And he says that the "filter bubble" also manifests in what kind of content people share. "Only 7 percent of the content folks click on on Facebook is 'hard news,'" he says. "That’s a distressingly small piece of the puzzle. And it suggests that 'soft' news may be winning the war for attention on social media — at least for now."

Since this study only measured people who felt strongly enough to list a political orientation — a number Bakshy puts at 9 percent — it's possible they're not representative of Facebook users at large. "What we do know is that moderates are quite similar to individuals who do not self-report, and that moderates look just like conservatives and liberals on their behavior on Facebook," says Bakshy. "But it is an interesting question to consider."

"Both liberals and conservatives have the potential to be exposed to content from the other side."

There are also subtleties that Facebook's automated analysis can't see. It can't tell, for example, if you're reading the summary and headline of an article but not clicking through. And since political alignment is based on general averages, it's not a measure of "spin" or even slant. "It's possible that we're classifying things as liberal when it actually doesn't contain any kind of slant or bias," for example, says Bakshy, because it comes from a source that's primarily read by liberals. "Some of the Huffington Post's articles are fairly neutral, but some are fairly polarized." Eventually, he'd like to look more deeply at single issues like gun laws or reproductive rights. But he's also optimistic that even if politics are polarized, the echo chamber isn't impenetrable. "Both liberals and conservatives have the potential to be exposed to content from the other side and do in fact click on content from the other side," he says.

Facebook isn't a good proxy for the larger "filter bubble" or even other social networks. It's often based around multiple circles of friends who know each other through completely separate offline interests, while people may join a network like Twitter specifically to talk to people they don't know. It's also hard to tell how this compares to the offline world. Is the internet helping people share news they might not in a face-to-face conversation? Or is it letting us curate our experiences to fit our own opinions?

Although this is far beyond Facebook's scope, Bakshy thinks Facebook might help us start to study it. "This is the first time we've really been able to measure how much people could be and are exposed to information from the other side," he says. "There's been no way to measure this in the offline world, and we've been able to do this for the first time in the online world at a very granular level."

Update May 7th, 2:30PM ET: Added comment from Eli Pariser.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15361468/LL6C9984-hero.0.1431018153.jpg)