Dave Mortimer went house shopping in 2013, and he made Internet speed a top priority. His standards weren’t incredibly high—he just wanted 20Mbps or so to make sure he could avoid some trips to the office.

“I work in IT, so fast speeds are essential for me to work at home,” Mortimer told Ars. “I called AT&T on three separate occasions to verify that this home had U-verse capabilities or, at the very least, 20Mbps. I was told every single time ‘Yes, that service is available at that residence.’” (When contacted by Ars, AT&T was unable to comment on what company representatives told Mortimer in 2013.)

Mortimer also plugged the address into AT&T's U-verse availability checker. The system reported that the home could get the service he wanted, Mortimer said.

But Mortimer learned the truth after moving into the house in Lowell, Michigan, a city of about 4,000 residents. Instead of AT&T’s U-verse fiber-to-the-node service, which could have provided up to 45Mbps, the best AT&T could actually offer him was up to 768kbps download speeds over DSL lines.

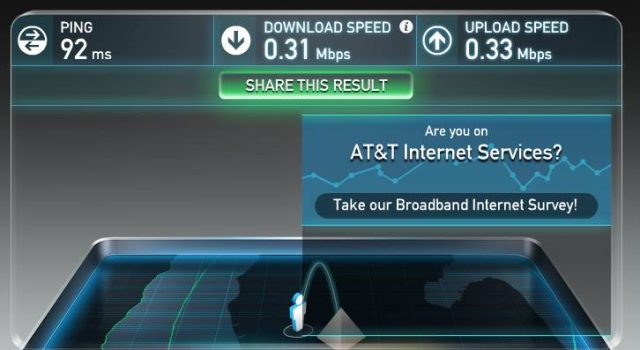

Since it was the only wired Internet option available, Mortimer subscribed. He soon found that the "up to" in AT&T's description was there for a reason; Mortimer said he could only get about 300 to 400kbps, a fraction of the 25Mbps download speed that meets the US definition of "broadband."

“Half the time, websites won’t even load,” he said. At those speeds, streaming video is out. Downloading files was difficult not only because of the low bit rate but also because the connection was often unstable, dropping many times a day.

Mortimer’s job involves helping employees with problems and maintaining the network.

“I go to an office most of the time but I’m on call at home, and the office is 30 minutes away,” he said. Getting work done at home requires logging in to a remote desktop. With AT&T, what should be 5-minute fixes could take 45 minutes, he said. Just restarting a server felt impossible from his home connection, so Mortimer made a lot more trips to the office than he'd like.

Fiber to 100 cities, but none in Michigan

In more lucrative areas than Mortimer's town, AT&T has made sure to bring fiber closer to homes. In 100 cities, all outside Michigan, AT&T says it is considering building fiber-to-the-home gigabit service, more than 2,000 times faster than the real-world speeds it delivered to Mortimer.

“Before we moved out here we had Netflix and Hulu and played online games, and now we don't do any of that,” Mortimer said. “We had to cancel a lot of subscriptions.”

Mortimer complained to AT&T and even to the state Public Service Commission and Federal Communications Commission about what he believes to be deceptive statements made by the Internet provider. Though he never got better Internet service from AT&T, the company eventually updated its website so that it no longer promised fast broadband to his residence. "After my complaint and their site evaluation, they corrected it on their website," he said.

Mortimer has appeared in front of the Lowell City Council to argue that the city should build its own fiber network, and he started a group called the Lowell Fiber Initiative to pursue that goal.

Spurned homeowners have little recourse

Ars first spoke with Mortimer in January. His situation recently took a turn for the better when, after much trouble, he was able to get usable wireless service at his house (more on that later).

The frustrations he experienced illustrate a risk taken by new homeowners, particularly in areas where Internet coverage is spotty. Even when home buyers call local broadband companies to find out whether service is available, they sometimes get incorrect information.

In Kitsap County, Washington, a man whom we wrote about last month said he was told by both Comcast and CenturyLink that he could get service at his house, only to find out that neither company could deliver. Comcast wanted him to pay $60,000 in exchange for extending their network to his house; instead, he decided to sell his house and move.

Last November, we wrote about Jesse Walser of Pompey, New York. His family uses a cellular hotspot for all its home Internet needs, because Time Warner Cable wanted him to pay $20,000 for construction costs.

Similar stories keep cropping up. “When I moved to my house in Florida, I knew Comcast was all over the neighborhood, and my new house even had a Comcast pedestal in the driveway,” telecommunications consultant Doug Dawson wrote on his blog last week. “But it took what felt like 40 calls to Comcast to get them to come out and give me a 40 foot drop wire. We started out with them not knowing if they serve my neighborhood until finally they decided to charge me $150 to verify that I could get service. Even with that, it took me over a month from the first call until I had working broadband—and a lot of people are not willing to suffer through that ordeal. I know it soured me on Comcast, and no matter what good they ever do for me, I will always have in the back of my mind how I had to practically threaten them to get them to give me service.”

Kimberly McCain, a small business owner in Tennessee, reported similar problems with AT&T. McCain attempted to switch from Comcast to AT&T, but after ordering DSL service and getting a self-install kit delivered, she was unable to get service. After weeks of back-and-forth with AT&T—during which she relied on a mobile phone hotspot because she had already canceled her Comcast Internet—“I was transferred to a ‘lead’ customer service rep that told me sternly, service was not offered in my area, period,” she wrote.

If providers prove unreliable, customers might hope that accurate information can at least be found from neighbors or previous owners. That's not always the case, either. McCain wrote that she lives in a very populated area, and she decided to subscribe to AT&T on the advice of neighbors who had the service, including one just five houses down the street. That made it all the more perplexing when service wasn’t available at her home.

In Mortimer’s case, the previous owners were a retired couple who apparently had no service, he said. Mortimer purchased the house in an estate sale. "The neighbors were elderly and didn't use the Internet, I guess,” Mortimer said. “One said they heard of a wireless service called Red Frog, but they actually don't exist anymore. AT&T said they offered it, but I didn't think I had to do their job for them and survey the neighbors to see if service actually existed.”

reader comments

303