A few years ago, when Joshua Landy and two colleagues wanted to create an app for doctors to share photos of their patients, their first step was hiring a lawyer.

They were right to be concerned. In the United States, strict so-called HIPAA laws make it illegal for doctors, hospitals, or insurance companies to divulge anyone's personal medical information without consent. Similar laws exist in Canada and other countries.

But these privacy rules do not extend to photos of unidentifiable people. So Landy's team created tools within their app to help doctors remove any personal details, such as faces or tattoos.

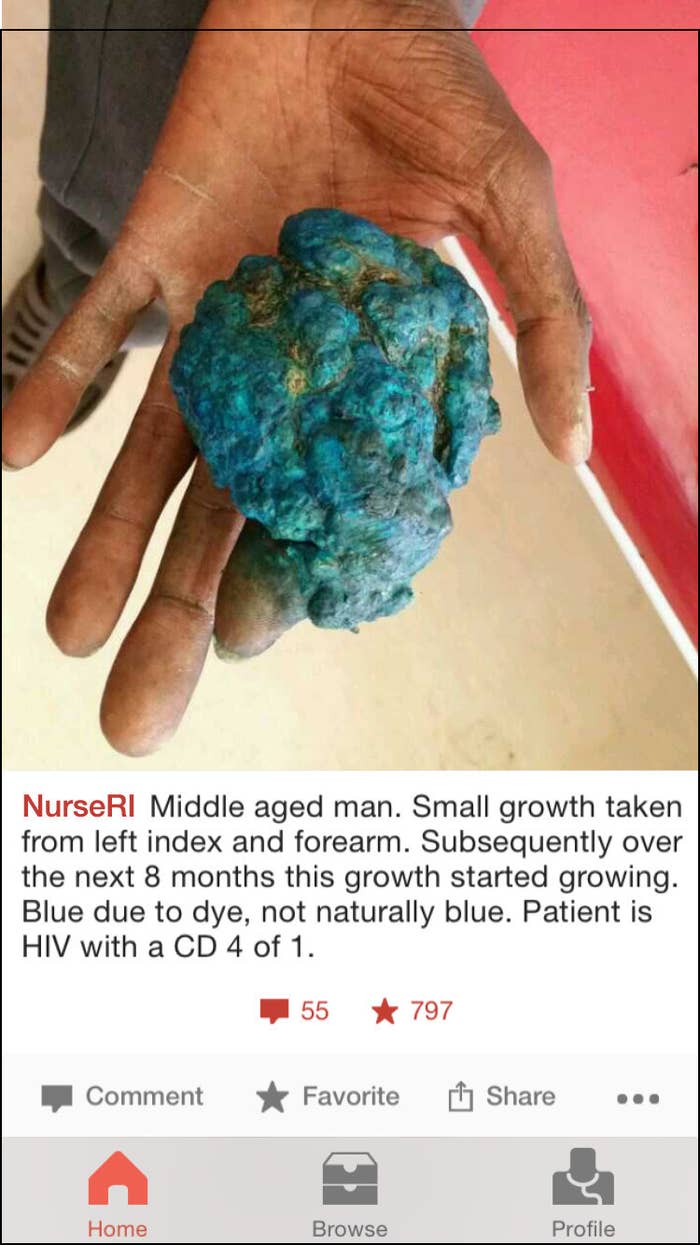

Today the app, called Figure 1, is perhaps better known as the "Instagram for doctors." It has hundreds of thousands of users in nearly 100 countries. Doctors post photos — such as graphic shots of rashes, gallstones, oozing infections, and an arm that had been caught in a tortilla slicer, just to name a few — with short captions sometimes noting the patient's age and sex. And they make comments on others' photos, ranging from quick-and-dirty diagnoses to off-color jokes. The images are viewed more than 3 million times a day.

More than 40% of all U.S. medical students use the app, according to Landy, a testament to its power as a teaching tool. But he says it's useful in the clinic too. On Thursday, Figure 1 announced a new feature, called "Paging," that allows doctors to instantly request specialists to comment on specific photos.

"It creates what we're hoping will be a network of hundreds of thousands of health care professionals who can gain access to the knowledge and experience of specialists at any time, anywhere in the world," Landy, an intensive care doctor in Toronto, told BuzzFeed News.

But many experts in health law and ethics, as well as many doctors, feel uneasy about Figure 1 — especially as its network grows. Anyone can download the app and view the photos, and Landy said non–health care professionals make up about 10% of users. Critics say that doctors who post photos may open themselves (and their hospitals) up to legal liability, whether for violating patient privacy or for suggesting an inappropriate diagnosis.

The biggest issue is that doctors don't necessarily ask their patients' permission before snapping their photos and posting them to the app. When doctors upload a photo, a button pops up that will lead them to consent forms. But the app does not store them or collect any data on how often they are used.

And even when patients officially consent, it's not clear whether they truly understand how widely their photos will be shared.

"I'm not sure why this is open to the public," Nicolas Terry, a law professor at Indiana University who specializes in health, told BuzzFeed News. "Because I think that does pose the question: Is this a professional site, or is this thinly disguised medical porn?"

The app's Terms of Service does not allow users to take screenshots, but the company's "image of the week" tweets give a good sense of the images:

How would you approach the keloids seen in our #meded image of the week? https://t.co/lH0xPzTSC7

Do you recognize the rare malformation seen in our #meded image of the week? https://t.co/rT804ofm91

Our #meded image of the week gives a rare look into #EVLP. Learn more: https://t.co/vrS3hlX9sl

Which genetic syndrome is complex syndactyly unique to? See our #meded image of the week: https://t.co/CHR2vrFNOG

Doctors have a long tradition of sharing patient information with each other for teaching and research.

Operating room galleries, for example, allow trainees to watch surgeries in action. And many print books contain photos of patients. Smith's Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformation contains hundreds of photos of babies and children, often with black bars over their eyes.

But the internet, and particularly smartphones, has made doctor sharing much easier and more frequent.

Landy came up with the idea for Figure 1 in 2012, when he was doing research at Stanford Hospital about how doctors use smartphones. Most of the time, he found, they were using their phones to take photos of their patients. These docs shared photos sometimes to seek advice, and other times just to educate others, he said. "Because some things are particularly unusual, complex, or sometimes textbook-perfect versions of things you'd only heard about in med school."

If what Landy found at Stanford is true in most hospitals, then doctors are sending each other photos "tens of thousands of times every day," he said. "And they're not doing it with any sense of protecting the patient's privacy, necessarily. It's also not being done in a way that necessarily preserves or archives those types of images."

Several doctors told BuzzFeed News that, indeed, they often text photos of patients to each other without worrying about HIPAA compliance. It's perhaps no surprise, then, that Figure 1 has taken off.

"I find it extremely interesting and I look at it pretty regularly," Laurie Morrison, a vascular surgeon from Washington state, told BuzzFeed News. It reminds her of email listservs she was on during her training in the late 1990s, on which small groups of doctors would ask for advice. With one big exception: "Those weren't visible to thousands and thousands of people."

Morrison said she regularly takes photos of her patients, with their verbal consent. But she has never posted a photo to Figure 1, partly because she finds it ethically troubling.

She cites one photo she saw on Figure 1 of a woman with a double vagina. Another showed a woman with a "huge fistula" between her vagina and rectum. The caption noted she was mentally ill, meaning that she probably couldn't give proper consent, Morrison said. Other photos show people with gunshot wounds (#GSW) to the skull, face, hand, and testicles.

If doctors are going to post patient photos, they should make sure to get explicit consent from their patients first, she added. "There may be places where it's not a legal issue, but I think it's a moral hazard no matter where you are."

@Figure1 app is ruining my life, BUT I CANT LOOK AWAY GUYS. I CAN'T.

Thanks to medical friends I will never be able to unsee @Figure1 images. My eyes are scarred forever.

In some places or situations, doctors do not need to get consent before taking or sharing patient photos.

BuzzFeed News asked a dozen of the country's largest hospitals about their policies on doctors taking photos of patients. Just two, Johns Hopkins in Baltimore and Jackson Health System in Miami, responded with clear policies. At both institutions, doctors must obtain written patient consent before sharing photos publicly. (The Johns Hopkins representative added that consent is not required when doctors are taking photos as part of medical care.)

"I would expect hospitals and other health care institutions to look at this [app] quite skeptically and probably prohibit their physicians from doing this," Terry, the law professor, said. There have been many private lawsuits in the U.S. against doctors who took photos of their patients, he added. "The courts have routinely been quite tough on this kind of stuff."

In addition to potential privacy violations, there's the question of liability, both for doctors who are posting photos and those commenting on them, Terry said. "Is the legal risk huge? No. Would I give physicians a green light to do this? No."

Outside of the legal realm, this app could change the nature of the physician-patient relationship. "Figure 1 creates the possibility of the public observing conversations that, previously, clinicians mostly had with one another behind closed doors," Michelle Meyer, an assistant professor at the Union Graduate College-Mount Sinai Bioethics Program, told BuzzFeed News by email.

Some comments "seem to revel a bit in the macabre of the blood and guts," Meyer said. "And in fact many, many posts do not seek a diagnosis or second opinion or even share information that is useful in any obvious way but instead appear to be posted mostly as something to gawk at."

These questions will only become more pressing as social media becomes more pervasive in our daily lives. Many doctors and hospitals are running social accounts as part of patient outreach.

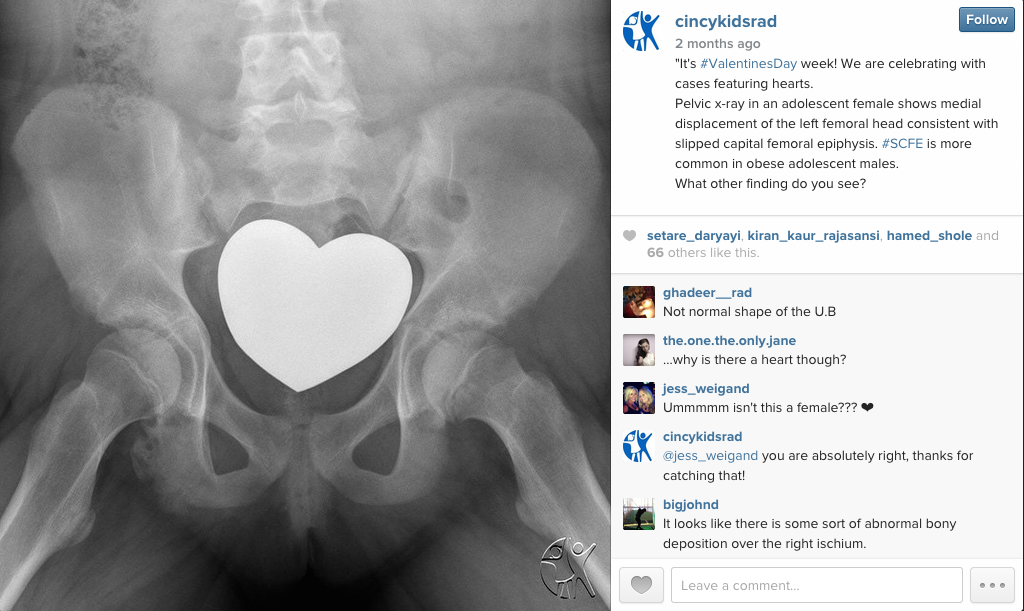

The radiology department of Cincinnati Children's Hospital, for example, has active Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Figure 1 accounts.

The two doctors who manage these accounts, Alexander Towbin and Saad Ranginwala, say they use them primarily as a way of educating other professionals. They make sure not to post pictures of patients who were in the news or who could be identified, they said, but do not ask for explicit consent before posting.

At Cincinnati Children's, doctors do occasionally take photos of patients with their smartphones, though "we try to discourage that," Towbin said. "It's one area where technology is really outstripping ethical guidelines."

Landy says his team has not yet figured out how to make money from Figure 1, though that is eventually the plan. (The company has received several million dollars in venture capital.)

The ultimate goal of the company, Landy said, is to bring people wider access to the medical world. He made the app open to the public, he said, partly because he wants to be transparent about how doctors work.

"There's a huge amount of opacity in the way medicine is practiced, generally," Landy said. "The images might be shocking to people who aren't used to seeing these things, but to 34 million health care professionals, this is just another day at the office."