The rise of automation has made the ad-buying and selling process more informed and efficient, but it’s also provided an outlet for fraudsters to profit.

After all, if machines conduct more transactions that used to take place between two humans over the phone, there’s less human oversight.

Additionally, ad ops teams, excited by the ability to buy lots of traffic at very cheap prices, sometimes overlook the need for due diligence. On the sell side, publishers need to increase audience to ensure incoming ad revenue. When they make decisions based on driving traffic into their digital domains, they often work with third parties, many of whom harbor fraudulent, nonhuman traffic.

While this helps advertisers meet basic KPIs around impressions and views, it also causes the quality of the ads to drop (since nonhuman traffic doesn’t actually buy product). When ad quality drops, publishers need more traffic, thereby creating a vicious cycle in which only the fraudster profits.

What is the working definition of ad fraud?

Generally speaking, ad fraud is nonhuman traffic or bots registering impressions or clicks on ad units.

However there is no official working definition of fraud and if you ask 10 different people in the industry, you’ll get 10 different answers.

Why is there confusion around the definition of fraud?

There’s disagreement on whether bad media placements constitutes fraud. For instance, a video ad running above the fold in a muted 1×1 iframe, or banners stacked on top of each other like playing cards could all technically be shown to a human audience, even though there’s no chance anyone will see those ad units.

Consequently, some industry players might argue that’s simply bad media placement. Others feel that’s a clear example of fraud.

Others believe no distinction needs to be made since in both instances, the advertiser did not get what it paid for and therefore was defrauded.

How bad is the ad fraud problem?

It depends on whom you ask. The more dire predictions state 40% of impressions traded on an open exchange or mobile clicks or some other online advertising KPI come from fraudulent sources.

Skeptics say the unusually high number comes from vendors hoping to peddle anti-fraud technologies.

As one might expect, companies that specialize in ad tech software claim they identify higher rates of ad fraud. Ad exchanges or ad networks, on the other hand, claim concern around fraud is overstated.

That being said, the Association of National Advertisers (ANA) and ad fraud solutions provider White Ops this month collaborated on a 60-day study looking at the severity of bots. The study tracked 181 campaigns among 36 ANA members (including Walmart, Johnson & Johnson and Kimberly-Clark) and determined that bots cause 23% of all video impressions, 11% of display ads and would account for $6.3 billion in losses in 2015.

What are bots?

Bots are nonhuman programs designed to generate phony ad impressions or serve hidden, unseen ads – all while avoiding detection.

They often take over a consumer’s computers and run in the background. A collection of bot-infected computers is called a botnet.

The advent of bots reflect fraudsters’ growing sophistication. Whereas a few years ago ad fraud was relatively simple, faking individual impressions on ads that were served but not seen, bots now give fraudsters scale and the ability to conduct their activities stealthily.

Bots also do more than fire fake impressions. Some serve ads behind the scenes, such that no human audience can see them – though the advertiser is still charged as if they had. Others come to a website simply to pick up cookies, which enable them to be retargeted elsewhere.

Bots are also becoming better at mimicking the behavior of someone after he’s clicked an ad. For instance, a bot might go to an advertiser’s site and watch a video or fill out a lead-gen form, or sometimes try to complete a purchase, which sends a conversion code back to the advertiser.

These activities are enough to fool advertisers into believing they’re getting results from their ad campaigns. They will then increase spend, optimizing their media buy for what they believe is legitimate consumer interest, when in fact they are optimizing for bots.

Another way botnets can affect advertisers is through laundered ad impressions. As real people (whose computers are infected with bots) browse the Internet, the bots clone that behavior. Because their browsing habits mimic those of real people, they are harder to detect by anti-fraud systems that look at behavior to determine whether impressions came from humans or from bots.

Consequently, these bots might be retargeted or even whitelisted as quality consumers.

Why is fraud hard to detect?

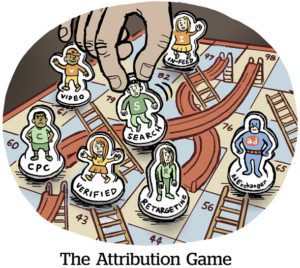

There are multiple points in the ad-buying process that are susceptible to fraud. Additionally, there are often multiple entities in the buying process, some of whom aren’t contributing to the sale in a clear way.

Basically, because fraudulent traffic washes through so many middle men, it’s very hard to follow the money to the original bot operator.

Additionally, botnets have varying degrees of sophistication. Some are easy to detect. The best ones aren’t. Weeding out numerous fraudsters is great, but it can create a false sense of security because the more sophisticated entities remain undetected.

In the words of Verbal Kint: “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.”

Are premium sites affected?

Yes. Ad fraud doesn’t just come from low-quality or fake websites. Even advertisers buying premium inventory can be affected by bots.

For instance, major publishers with affiliate deals will often buy traffic, working with an audience platform or a third party full of bots. Because these deals are meant to increase volume, the publishers unwittingly open the door to bot traffic, serving premium impressions to nonhuman entities.

Advertisers using last-touch attribution can be particularly affected by this type of fraud, since publishers serving more impressions – even if those impressions are nonhuman – have a greater chance of correlating themselves to a conversion.

Are there other types of ad fraud besides bots?

Yes, though bots are the most prevalent type of ad fraud. Other types of fraud include:

- Laundered ad impressions – Impressions from sites with large amounts of human traffic are rerouted through fake content sites or piracy sites – where most advertisers don’t want to purchase units.

- Impression stuffing/Ad stacking – Publishers might layer multiple ads on top of a single ad slot. Only the top one is actually seen by a consumer. Or a publisher might jam a bunch of ads in 1×1 pixels, which fire as if they were seen even if they actually weren’t viewed at all.

- Cookie stuffing – Cookie stuffing can happen when websites send visitors to affiliate marketing programs. If the visitor completes an action like a purchase or filling out a form, the referring website gets a cut. These websites use cookies to legitimately track a user’s activity. However, fraudsters might add illegitimate cookies to get a cut of that paid commission. One way they can do this is by buying reams of nonviewable or low-quality impressions to generate a false “view through” in order to gain fractional credit along a consumer’s path to purchase.

- Fake sites – Fake sites are built simply for advertising and offer no content that real human audiences want to see. Many fake sites are also part of a greater network. Each individual site doesn’t collect an inordinate amount of revenue, which is how they avoid suspicion. But networks of fake sites can derive millions in revenue from their activities.

- Fake domains – Fraudsters will spoof the domains of high-profile, in-demand sites. Advertisers think they’re buying placement on premium publishers, when they’re really not. This practice also makes it seem as if premium publishers have more inventory than they actually do, which decreases their prices.

- Toolbars – While toolbars had their heyday in the ’90s and early 2000s, they’re still around and inject their own ads over the legitimately purchased units on websites. As with proxy sites, they often give advertisers the illusion that they’re buying better inventory than they actually are.

What’s the situation with ad fraud in video?

Video is an extremely alluring target for fraudsters, since the format provides higher CPMs than either display or mobile.

While there are certain tells in video interactions that indicate fraud – for instance, clicks are usually bots because humans rarely click on a video – video ad fraud requires a higher level of coding expertise. These coders, whom White Ops CEO Michael Tiffany described as “the badasses of ad fraud,” create stealthier, more sophisticated fraud mechanisms.

The video ad environment is also highly conducive to fraud. Simply put, there’s more advertiser demand for video inventory than publisher supply, which provides the perfect opportunity for fraudsters to rush in and artificially fill that gap.

What about mobile?

Right now, mobile budgets are still considered small potatoes, which is why the ad industry isn’t actively worried about mobile ad fraud.

But as mobile budgets grow, the ad tech industry certainly anticipates an influx of fraudulent activity. However, there aren’t many studies examining mobile ad fraud’s proliferation (the ANA/White Ops joint study did not include the channel).

Mobile also presents its own unique challenges because its largely cookieless mobile browser environment makes it more difficult to measure. Additionally, different mobile operating systems have different technological challenges, as does the mobile app environment.

While anti-fraud vendors haven’t seen much mobile ad fraud, it’s possible that their tools aren’t mature enough to have the necessary visibility.

Will the ad fraud problem ever go away?

No. It’s low-risk, high-reward. Many fraudsters live outside of the United States and it’s not exactly the sort of criminal activity that elicits a crackdown from law enforcement.

Which vendors have solutions that prevent fraud?

There are multiple vendors that tie ad fraud solutions with their analytics or ad-serving stacks. Among them are Sizmek, Moat, Telemetry, comScore, Videology, Dstillery and Pixalate. However, there are also a handful of vendors who focus specifically on ad viewability and ad fraud (the two are closely related given the blurred line between fraud and bad media).

Following is a summary of four pure play ad fraud/viewability solutions providers.

DoubleVerify’s integrated viewability and ad fraud solution is designed to authenticate the quality of digital media for advertisers.

Its tools are designed to block either entire sites that have a reputation for fraud or individual impressions for advertisers that don’t want to cut off an entire inventory source. To identify nonhuman browsers, DoubleVerify looks at hundreds of data points around a specific user as it interacts in multiple online environments.

Because DoubleVerify’s ad fraud solution is rolled into its viewability solution, it enables advertisers to determine ads that weren’t viewed because of bad placement vs. impressions that came from fraudulent sources.

Forensiq works primarily with DSPs and agencies (and some brands) to prevent fraud before it happens. While it does post-buy reporting, it has a solution that is designed to return a risk score on an impression before the bid even happens. To do this, it looks at the reputation of traffic sources or the publisher domain. Forensiq stores records of spoofing characteristics from different sources in a global database.

Since fraudsters often hide behind legitimate domains, Forensiq has what it calls “proxy-piercing capabilities,” designed to show when domains or browsers are being spoofed, ultimately revealing the botnets or malware-infected computers sending traffic to the site.

Forensiq also looks at the entire consumer buying funnel – from impressions to clicks and conversions – rather than focusing on a single aspect like bots. This means its system is designed to detect an array of fraud and bad media.

Integral Ad Science provides technologies and services around ad fraud and media quality to both the buy and sell side. Its technology looks at about 3.5 billion impressions per day and examines behavioral patterns, at the impression level, to identify machines infected with bots.

It also serves as an intermediary in disputes between advertiser and publisher. If publishers violate certain aspects, like placing ads in geographies the advertiser doesn’t want or purchasing fraudulent impressions, then Integral steps in proactively to try to fix the problem.

It has what it calls a “real-time actionable solution,” meaning it picks up campaign anomalies within a day, instead of weekly or campaign wrap-up reports. This prevents advertiser clients from spending on bad or fraudulent media.

White Ops is able to detect bots because its service is integrated in each web session, meaning that part of White Ops’ service is downloaded when an ad is displayed – whether on desktop, mobile or video.

The technology is designed to drill deep enough to tell the difference between a real impression from a human over a fake impression, even if both come from the same computer.

White Ops also works with ad exchanges and networks that want to kick out fraudulent players, like fake websites.