The Psychology of Healthy Facebook Use: No Comparing to Other Lives

How to break tendencies toward social comparison

Do you ever go to parties just to look at beautiful people and listen to them chatter about their lovely lives? Lives punctuated only occasionally by some glitch—maybe a death in the family, or a social injustice that warrants reprimanding of societal power structures—but even in those moments the people are brimming with compassion, empathy, and insight? And you just show up and stare and listen and stare.

Such is the Facebook experience for many people, according to psychologists at the University of Houston and Palo Alto University. While using Facebook has been shown to provide needed self-affirmation and to further improve the quality of already-good romantic relationships, these researchers published two studies that—along with another one from applied social psychologists at University of Cologne in the same journal this week—seem to confirm an association between Facebook use and depressive symptoms. (Not depression in the debilitating clinical sense, but milder manifestations.)

"Other studies have established links between Facebook and depressive symptoms, but we're trying to figure out, why do people feel this way?" said lead researcher Mai-Ly Steers, a doctoral candidate in Houston who is one month away from her Ph.D. "What these two studies reveal is that the underlying mechanism is social comparison. That's why the more time we spend on Facebook, the more likely we are to feel depressed."

In the 1950s, the psychologist Leon Festinger popularized social-comparison theory. He argued that people have innate tendencies to track our progress and assess our self-worth by comparing ourselves to other people. That social comparison leads to feelings of insignificance and insecurity. Research has since found that making social comparisons, especially "upward" comparisons (to people we deem above us, to whom we feel inferior, for whatever reason) are associated with negative health outcomes like depressive symptoms and decreased self-esteem. Because Facebook tends to serve as an onslaught of idealized existences—babies, engagement rings, graduations, new jobs—it invites upward social comparison at a rate that can make "real life" feel like a modesty festival.

In their latest studies, the psychologists conclude that their work "holds important implications for general populations and, in particular, college students [the participants in these studies] who are depressed and might also be addicted to Facebook. Future interventions might target the reduction of Facebook use among those at risk for depression."

I talked with Steers about what a person can do to avoid that kind of negative relationship with the book of faces.

James Hamblin: Should everyone de-friend all of their successful friends?

Mai-Ly Steers: I don't think you should, necessarily. If you have a healthy amount of self-esteem, why not [keep them]? It might motivate you to be better.

Hamblin: Does your model discount the reversal of the Facebook-depression correlation—that people might spend more time on Facebook when they are lonely and sad?

Steers: It could be possible, but we tested that, and didn't find a strong relationship. Not to say that doesn't occur.

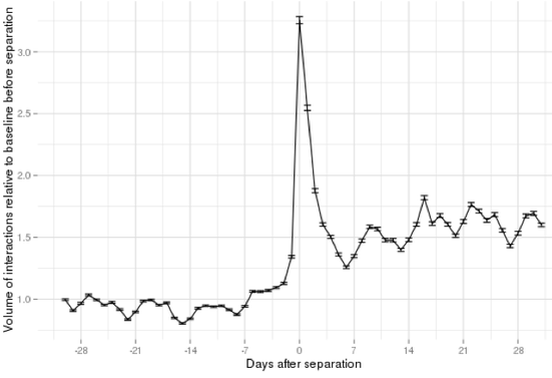

Hamblin: Facebook did release some data that said that after a breakup, the amount of time people spend on the site goes crazy.

Facebook Interactions Before and After Breakup

But that doesn't mean people are sad. Maybe they're elated.

Steers: I got into this line of research after my sister wasn't able to go to a school dance, and she was really upset. After looking at her friends' feeds the next day, she got even more distressed, and I thought, this might be a common occurrence.

Hamblin: You hadn't felt it yourself? Do you not use Facebook?

Steers: I do. I'm more aware of it now. I think everybody feels it to a certain degree. The thing about it is, you never have any idea what you're going to be socially comparing yourself to, because you don't know what your friends are going to post. And what I would compare myself to wouldn't necessarily be what you would compare yourself to.

Hamblin: I would compare myself to someone who had a really good sandwich. Other people might compare themselves on life goals, like graduating from a doctoral program.

Steers: I guess it depends what your priorities are. That's what social comparison theory is all about.

Hamblin: When I saw this I thought about how the Facebook-feed algorithm prioritizes popular posts that other users engage with, which tend to be new babies and graduations and new jobs—while the "I ate a sandwich today" posts get buried because no one else seems to like them—so that could end up skewing your perception of how much great big stuff your friends have going on.

Steers: Part of the reason for that is people tend to self-present on Facebook.

Hamblin: No!

Steers: They try to present themselves in the best light possible. The title of my paper is "Seeing Everyone's Highlight Reels."

Hamblin: So maybe everyone could just agree to post things that are only mildly interesting? So everyone's lives seem accurately quotidian and banal?

Steers: I've seen pictures of people's Subway sandwiches. It really depends on the person and what they feel is important.

Hamblin: Nobody likes Subway pictures, though. It's like a no-win game. If you only post the big things, people will think you're too polished and only come on Facebook to brag and get attention. If you post other stuff, you're boring.

Steers: Are you looking for a takeaway message?

Hamblin: Always.

Steers: So, I use a quote from Theodore Roosevelt to preface my article: "Comparison is the thief of joy."

Hamblin: What if you only compare yourself to people who make you feel superior? Like someone who just failed out of a graduate program? And you check their page every day, to feel better about yourself? You write about how downward social comparison, seeing yourself as better off than or superior to others, has been associated with positive health outcomes: less anxiety, positive self-esteem, and positive affect.

Steers: Well, that's more defensive self-comparison. Other literature suggests that the relationships between social comparison and well-being is more complex than simply the direction of the comparison. It's the act of frequently socially comparing oneself to others, rather than the direction, that's related to long-term destructive emotions. Any benefits gained from social comparison is probably temporary, whereas frequent social comparisons of any kind are linked to lower well-being. You would still feel bad in the end.

But that encapsulates the whole idea: I don't think Facebook is innately good or bad. I think it's all in how we use it. If we use it to connect with other people, which i it's intended purpose is, right ...

Hamblin: Or to make money for Mark Zuckerberg and build unimaginable power by controlling all news and entertainment media.

Steers: Well, if every time we open our Facebook, we find ourselves socially comparing and feeling bad, then I think you have to reevaluate. If there are negative consequences, take a step back and see if Facebook is right for you. Are the connections you're making there worth the negative elements?

We used to have different spheres in our lives, specifically work and home, maybe church. Now they just all collide on Facebook.

Hamblin: So when you're posting things, it's hard to know your audience. I think Google tried to break that down with circles on Google Plus.

Steers: Facebook offers that, too. But how many people actually use it?

Hamblin: I don't know! I don't know what other people's Facebook experiences are like. I don't think a lot of people poke. I do.

Steers: I do think people post indiscriminately, and they forget their audience. But, really, I don't think this is about the medium itself. It kind of irks me when people take away from this, oh, Facebook causes depression. The medium is just an extension of our genuine human tendencies. Maybe they're heightened, because in the world you don't have a constant barrage of this information about other people, which can be jarring. Especially if you weren't expecting, for instance, a certain person to get engaged, and how happy they are, and how surprised they were, and you just broke up with someone.

Hamblin: In real life, if that person knew your story, they wouldn't bombard you with their happiness right up front. So how do people get out of the comparison mindset? Beyond swallowing aphorisms about it being joyless.

Steers: One good approach is that the antidote to comparison tends to be gratitude. If you're grateful for things, you're not really comparing yourself.

Hamblin: You can be grateful for having that successful, beautiful, flawless person in your life.

Steers: Or for your own life, and your own successes. If you really are grateful, then other people's successes shouldn't bother you as much. Maybe.

Hamblin: So someone else can write on Facebook about how they just got a new Ferrari, and I can think, hey, at least I am still breathing.

Steers: Maybe you could think about borrowing that Ferrari. Be grateful for the opportunity to drive their Ferrari without having to buy one.