OAKLAND, Calif.—Over the last two years, the Oakland Police Department (OPD) has disciplined police officers on 24 occasions for disabling or failing to activate body-worn cameras, newly released public records show. The City of Oakland did not provide any records prior to 2013, and the OPD did not immediately respond to Ars’ request for comment.

The records show that on November 8, 2013 one officer was terminated after failing to activate his camera. Less than two weeks later, another resigned for improperly removing the camera from his or her uniform. However, most officers received minor discipline in comparison.

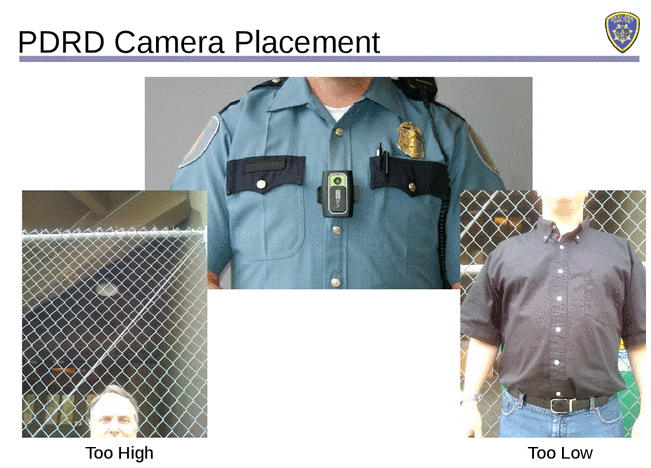

The OPD has used Portable Digital Recording Devices (PDRDs) since late 2010. According to the department's own policy, patrol officers are required to wear the cameras during a number of outlined situations, including detentions, arrests, and serving a warrant. At present, the city has about 700 officers.

This year the issue of body-worn cameras on police officers came to the fore after the tragic killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York City at the hands of local cops. In the aftermath of grand jury decisions to not indict the officers responsible, the Obama administration released a review of how local law enforcement agencies use equipment, proposing that the federal government spend $263 million over three years to "expand training for law enforcement agencies (LEAs)" and "add more resources for police department reform." The review included a proposal to dedicate $75 million over three years to buy up to 50,000 body cameras for local LEAs.

Because body-worn cameras are still relatively new, there aren't any published studies on rates of non-compliance, according to John DeCarlo, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the former chief of police of Branford, Connecticut.

"You may have a legitimate excuse [for not turning it on], but if it was nefarious, that's a different story," DeCarlo told Ars.

What happened on November 22, 2013?

In Oakland, the cameras were acquired largely as the result of a federal lawsuit alleging abuse by four officers known as "The Riders." In 2003, the City of Oakland and the OPD agreed with the plaintiffs to a settlement, which required the authorities to pay more than $10 million in fines and impose numerous reforms. The four officers were subsequently fired from the OPD, although one remains a federal fugitive after fleeing to Mexico. None of the other three officers were convicted.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...