The cable lobby is opposed to a Federal Communications Commission plan to define "broadband" as speeds of at least 25Mbps downstream and 3Mbps up.

Customers do just fine with lower speeds, the National Cable & Telecommunications Association (NCTA) wrote in an FCC filing Thursday (thanks to the Washington Post's Brian Fung for pointing it out). 25Mbps/3Mbps isn't necessary to meet the legal definition of "high-speed, switched, broadband telecommunications capability that enables users to originate and receive high-quality voice, data, graphics, and video telecommunications using any technology," the NCTA said.

"Notably, no party provides any justification for adopting an upload speed benchmark of 3Mbps," NCTA Counsel Matthew Brill wrote. "And the two parties that specifically urge the Commission to adopt a download speed benchmark of 25 Mbps—Netflix and Public Knowledge—both offer examples of applications that go well beyond the 'current' and 'regular' uses that ordinarily inform the Commission’s inquiry under Section 706" of the Telecommunications Act.

Hypothetical use cases showing the need for 25Mbps/3Mbps "dramatically exaggerate the amount of bandwidth needed by the typical broadband user," the NCTA said.

"Netflix, for instance, bases its call for a 25Mbps download threshold on what it believes consumers need for streaming 4K and ultra-HD video content—despite the fact that only a tiny fraction of consumers use their broadband connections in this manner, and notwithstanding the consensus among others in the industry that 25Mbps is significantly more bandwidth than is needed for 4K streaming," the NCTA said. "Meanwhile, Public Knowledge asserts in conclusory fashion that an 'average' US household constantly streams at least three high-definition movies simultaneously while also running various 'online backup services and other applications'—without providing any evidence indicating that such usage is at all 'average.'"

The commission defines broadband as 4Mbps down and 1Mbps up but hasn't changed the definition since 2010. The FCC is required under Section 706 to determine whether broadband is being deployed to Americans in a reasonable and timely way, and the commission must take action to accelerate deployment if the answer is negative. Raising the definition's speeds provides more impetus to take actions that promote competition and remove barriers to investment, such as a potential move to preempt state laws that restrict municipal broadband projects.

But changing the definition doesn't create any immediate impact other than lowering the percentage of Americans who have "broadband" and shaming Internet providers that don't offer broadband speeds. Even if the NCTA loses its battle to keep the lower broadband definition, it wants to make sure that any change has no real world effect.

"As an initial matter, the Commission should make clear, as it has in prior Broadband Progress Reports, that any speed benchmark it adopts has no regulatory significance beyond the new Report," the NCTA said.

The FCC does set a minimum speed for rural broadband projects that rely on Universal Service funds, but it settled on a definition of 10Mbps down and 1Mbps up for that purpose.

Verizon is also lobbying against a faster broadband definition. This is no surprise; while cable technology is robust enough to deliver 25Mbps/3Mbps, DSL speeds are far more limited in comparison. Verizon does offer fiber Internet service but much of its territory is still stuck on DSL.

Verizon told the FCC last week that broadband is already "being deployed in a reasonable and timely fashion." Verizon also wants the FCC to count cellular service as broadband alongside fixed Internet service, but FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler argues that mobile's pricing levels and data caps make it an unsuitable substitute for cable and fiber.

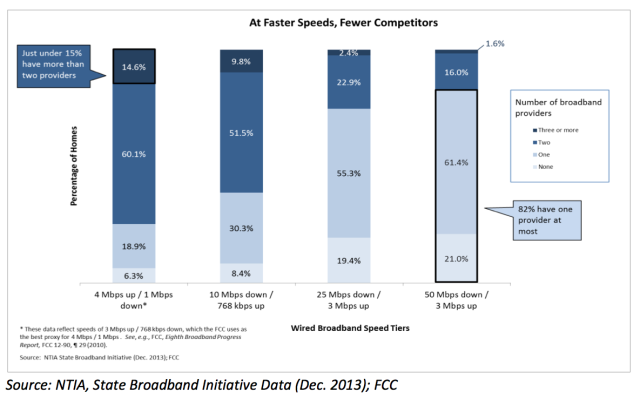

Though a majority of Americans can purchase broadband of at least 100Mbps, Wheeler has focused on the lack of competition at higher Internet speeds. While 75 percent of American homes have at least two options for wired broadband of 4Mbps/1Mbps, only 25 percent have a choice of at least two providers at the 25Mbps/3Mbps threshold:

25Mbps is becoming "table stakes" for modern communications, especially in homes that use streaming audio and video and have numerous devices connected to the Internet, Wheeler has argued.

The US Government Accountability Office recently urged the FCC to take action against data caps in wired broadband, but so far the FCC has not done so.

reader comments

275