In the first century of baseball’s history as an organized sport, a shortstop hit 25 or more home runs in a season 11 times. Ernie Banks, who died Friday evening at the age of 83, did it seven times — and all seven times, he hit 40 or more home runs.

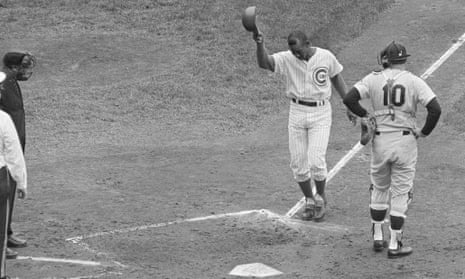

The sport of baseball knew him best for his all-encompassing joy — a love for the sport that Banks frequently punctuated with the expression, “Let’s play two!”, as in two games in one day. That smile, that happiness often obscured the simple fact that, by any measure used, Ernest Banks was a fantastically good player. He was so much more than a smile, a nickname, and a tagline.

In a 19-year career, all spent with the Chicago Cubs, Banks hit 512 home runs, had 1,636 runs batted in, 2,583 hits, and a career batting average of .274. As a shortstop, he was peerless; the sport had never seen anyone with his combination of power and grace playing shortstop, and it wouldn’t see a similar player until the 1990s, a decade defined by power-hitting at every position.

In contrast to today’s marbled, sculpted players, Banks didn’t look the part of a slugger; he was whippet-lean, and tall, at 6-1. From the start, though, it was clear that Banks had potential. His 1953 scouting report, filed by Hugh Wise, makes it clear:

Player’s strength: Ability, outstanding arm and good hitter.

Player’s weakness: No outstanding weakness.

Years before Major League: Can play now.

Two years after becoming the first black player in Cubs history, Banks picked up a teammate’s bat by mistake. He was shocked, yet pleased by how light it was. He explained why in his Hall of Fame induction speech:

“I went to the light bat partly by accident,” Banks said. “I was standing by the batting cage at the old Polo Grounds one day and picked up a 31-ounce bat Monte Irvin had acquired. I told Monte, ‘This feels good!’, and he said I ought to use one like it. The next day, I experimented with it in batting practice, and the ball was really jumping off the bat. I weighed only 160 pounds, but I could get terrific bat speed swinging that light wood. I hit five grand slam homers and a total of 44 homers.

“Pitchers kept telling me, ‘Ernie, you really can pull those outside pitches — how do you do it?’ Other hitters saw what was happening and began to switch to lighter bats. The light bat was my livelihood. It made me a hitter.”

That was the quintessential Ernie Banks — even in a moment of crowning glory, his innate humility suffused his heroic feats. In short order, Banks became the greatest power-hitting shortstop in baseball history. He did all that in just nine seasons of playing the position, before a knee injury in 1961 forced him to move to first base, where he spent the remainder of his career. He was an excellent fielder; Banks won the 1960 Gold Glove Award, and led the National League in putouts, assists, double plays and fielding percentage. But it was his hitting that simply takes your breath away, even today.

Banks’ offensive statistics as a shortstop are literally incredible. Those five grand slams? They set a major league record that stood for thirty years, before the Yankees’ Don Mattingly hit six of them in 1987. His 44 home runs sparked a mind-boggling five-year run in which he hit 44, 43, 45, and 47 home runs; he “only” hit 28 home runs in 1956. The 248 home runs Banks hit between 1955 and 1960 outpaced every player in major league baseball, including legendary sluggers like Mickey Mantle and Hank Aaron. You can argue that Banks was helped by playing in Wrigley Field, a small ballpark; but over that period, his road slugging percentages were .498, .504, .564, .533, .563, and .567.

During those nine years, he hit 123 more home runs than any of the 10 shortstops who preceded him into Cooperstown. His 512 career home runs are only 42 shy of the total number those ten shortstops hit. Over those nine seasons, Banks had a batting average of .290 with 37 homers and 106 RBIs for every 150 games. Before Banks, shortstops were defensive specialists, considered offensive liabilities; Banks revolutionized the position with pulverizing force. And he did it in an era when pitching, not hitting, was overwhelmingly dominant.

In 1958 and again in 1959, Banks became the first player in National League history to be crowned Most Valuable Player in consecutive seasons; he was the first player from a losing team to ever be honored in this manner. And man, did the Cubs lose during his career. In those 19 years, the Cubs posted only six winning seasons; more often, they were mired deep in the basement of the National League, with hopes of playing in the World Series crushed by July.

That changed in 1969. With four new expansion teams — the Montreal Expos and the San Diego Padres in the National League, the Seattle Pilots and the Kansas City Royals in the American League — both leagues introduced divisions. For much of the spring and summer, the Cubs led the new National League East. As late as August 16, they held a nine-game lead on the New York Mets. Banks, too, seemed rejuvenated; that season, aged 38, he hit .253 with 23 home runs and 106 RBIs, and was selected to his 11th All-Star team.

Then the Cubs became the Cubs, and the Mets became “Amazin’”. Between August 17 and September 10, the Cubs went 9-15, punctuated by an eight-game losing streak that saw them go from eight games ahead to two games behind. They never got closer than that, and the Mets went on to win the division, beat the Atlanta Braves in three straight games to win their first National League pennant, and shock the Baltimore Orioles in five games to win their first World Series.

That was also Banks’ last full season. He played 62 games in 1970, and just 20 in 1971, after which he retired. He never made it to the World Series, sadly. Even without that, though, Banks remains a staggeringly important player in baseball history. Forty-three years later, Banks is still the Cubs all-time leader in games played (2,528), at-bats (9,421), plate appearances (10,395) and extra-base hits (1,009). He is second in home runs, hits (2,583) and RBIs (1,636).

The astounding totality of his achievements are why Ernie Banks became known as “Mr. Cub”; his number, 14, was the first number retired by the franchise. In 1999, the Society for American Baseball Research listed Banks 27th on a list of the 100 greatest baseball players. In 2013, Banks was honored by another Chicagoan — President Barack Obama — with the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Now, Ernie Banks belongs to the ages.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion