Britain’s volunteer army will be out in force on Thursday, providing a Christmas dinner for the hungry, shelter for the homeless and a shoulder to cry on for the old and lonely. David Cameron calls this the ‘big society’ in action. His opponents say the reality is a cash-strapped charitable sector struggling to cope with a bigger caseload thanks to the government’s spending cuts.

As a concept, the big society is a good thing. Nobody could really object to the idea that people should be encouraged to help others. Those who will be running soup kitchens and hostels on Christmas Day deserve nothing but praise. There are sound economic reasons why the government should be encouraging people to volunteer. But they are not the ones normally used by Cameron and his ministers.

The thinking behind the big society is the same as the thinking behind the government’s economic strategy: the state got too big and “crowded out” the private sector. In the case of the economy, George Osborne believes that running a tight ship will lead to lower interest rates and so encourage the private sector to invest. In the case of the big society, the notion is that people have become so accustomed to the state intruding into areas that were once the preserve of the voluntary sector that they have become more selfish and so lost the instinct to help others. Scaling back the state will therefore “crowd in” private welfare provision.

The “crowding out” argument didn’t work for the economy. Interest rates were already low when Osborne became chancellor so cutting public spending and raising taxes had the effect of reducing demand. Lower demand made businesses more cautious about investing, and it has only been since the government boosted growth by re-invigorating the housing market that firms have been willing to spend more.

The idea that spending cuts will crowd in the big society is similarly flawed. Firstly, there is no record of this approach working in the past. According to research by Arthur Downing of Oxford University, periods of state cutbacks in the nineteenth century did not lead to a flourishing of community organisations. Austerity inhibited rather than encouraged the growth of self-help friendly societies.

Secondly, there is not an easy divide between the state and voluntarism. The charitable sector relies heavily on financial support from the government and has seen its funding pared back. It is hard to find a charity now that says it is not struggling to make ends meet. The cash crisis is particularly acute for those organisations that depend on local authority grants, the sector of state spending that has been most aggressively cut.

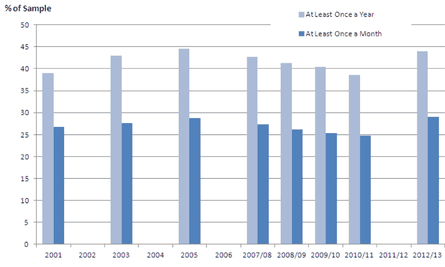

Finally, there is no real evidence that the willingness to volunteer has changed much over the years. If Cameron’s argument is that New Labour’s nanny state created a nation of self-centred couch potatoes, then that is not supported by the evidence. The percentage of the population volunteering once a month stood at just above 25% in 2001, rose a bit during the boom and then fell back to its original level when the financial crisis broke in 2007-08.

Volunteering is currently at a 10-year-high, but according to Andy Haldane, the chief economist at the Bank of England, it tends to go up and down (but only a bit) with the economic cycle. There are reasons to think the willingness to volunteer will rise; there is a greater tendency to volunteer among older people and their numbers will rise as the population ages. There also appears to have been a behaviour shift among young people, where participation rates have doubled in the past decade.

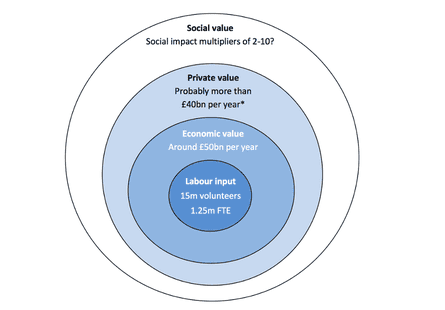

Haldane’s real point in a recent lecture, though, was to attempt to put a monetary value on volunteering in order to show just how much the willingness to do unpaid work benefits Britain. Around 15 million people volunteer regularly. They put in between them over 2bn hours a year, or on average just over an hour a week for every person over the age of 16. This is just formal volunteering, unpaid work for groups, clubs, charities or other organisations. It is estimated that the same amount of time is spent on informal volunteering, which might be running a neighbour to a doctor’s appointment or taking an elderly relative to do their shopping. Haldane says the economic value of volunteering could exceed £50bn a year – which would make it as big as the energy sector.

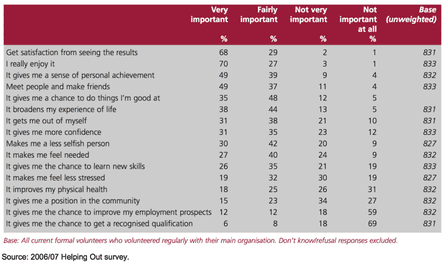

But that’s not the end of the measurable benefits. Individuals get a private benefit from doing things for others. They enjoy volunteering: it gives them satisfaction; it broadens their circle of friends; it boosts their confidence; reduces stress; makes them healthier; and teaches them new skills. Haldane says that the gains to the individual in terms of wellbeing, improved health and increased employability might exceed the £50bn-plus benefit to the recipients of volunteering.

In addition, there’s the social value of volunteering. Haldane provides the example of economists who worked with the charity Centrepoint to work out the value to society of reducing homelessness, through putting young people into work or training; by preventing them re-offending; by reducing the incidence of mental health issues; and dealing with substance abuse. For every £1 invested, there was a social benefit of £2.40.

Haldane puts it this way: “We have a volunteer army, the full-time equivalent of 1.25 million people, diverse in age, gender, background and ethnicity and potentially growing in number. They create each year economic value of at least £50bn and potentially higher. They create private value for individual volunteers of maybe as much again. And although the confidence intervals are large, it would not be unreasonable to apply a social multiplier of upwards of two to these estimates.”

The conclusion from all this is pretty simple. Individuals should be encouraged to volunteer because they could well be unaware of the personal benefits they will get from doing so. Businesses should be encouraged to provide the time for their staff to volunteer because they will end up with a more skilled, productive and better-motivated workforce as a result. He notes that while 70 of the firms in the FTSE 100 have employer supported volunteering schemes, that still means 30 do not. What’s more, there is only one director drawn from the voluntary sector for FTSE 100 companies.

Governments should be encouraged to promote volunteering because it improves wellbeing, meets a demand for services and makes people more contented. Cameron can rightly say that he is trying to flesh out the big society concept. One example is that since 2011, the civil service has been formally encouraging staff to spend one day a year volunteering. But let’s be clear. There is no binary choice here. A smaller state does not equal a bigger society.