Is One of the Most Popular Psychology Experiments Worthless?

A trolley is careening toward an unsuspecting group of workers. You have the power to derail the trolley onto a track with just one worker. Do you do it? It might not matter.

Harvard University justice professor Michael J. Sandel stood before a lecture hall filled with students recently and presented them with an age-old moral quandary:

"Suppose you're the driver of a trolley car, and your trolley car is hurtling down the track at 60 miles an hour. You notice five workers working on the track. You try to stop, but you can't, because your brakes don't work. You know that if you crash into these five workers, they will all die. You feel helpless until you notice that off to the side, there's a side track. And there's one worker on the side track."

The question: Do you send the trolley onto the side track, thus killing the one worker but sparing the five, or do you let events unfold as they will and allow the deaths of all five? (Most people, for what it's worth, say they would turn.)

Then Sandel asked about a popular variation on the same problem. The same trolley is careening toward unsuspecting innocents, but this time, you're an onlooker on a footbridge, and, "you notice that standing next to you, leaning over the bridge, is a very fat man."

A ripple of laughter rises from the packed auditorium.

"You could give him a shove," he continues. "He would fall over onto the track, right in the way of the trolley car. He would die, but he would spare the five. How many would push the fat man over the bridge?"

A few hands go up, but most of the students just erupt in giggles.

And that's exactly why, some scientists argue, this well-known "trolley dilemma," shouldn't be used for psychology experiments as much as it is.

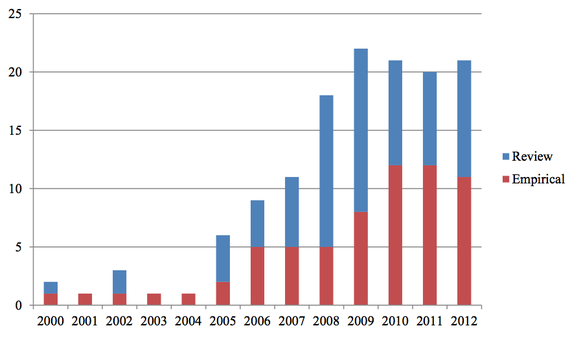

Over the past few decades, the trolley dilemma has been at the center of dozens of experiments designed to gauge subjects' moral compasses. Some people think it can help answer Big Questions about everything from the use of drones to self-driving cars.

One recent paper by Harvard's Joshua Greene and others, which involved MRI scans of people contemplating the trolley, has been cited more than 2,000 times. In 2007, the psychologists Fiery Cushman and Liane Young and the biologist Marc Hauser administered the test to thousands of web users and found that while 89 percent would flip the track switch, only about 11 percent would push the fat man.

That contradiction—that people find giving the man a fatal prod just too disturbing, even though the end result would be the same—is supposed to show how emotions can sometimes color our ethical judgments.

But one group of researchers thinks it might be time to retire the trolley. In an upcoming paper that will be published in Social and Personality Psychology Compass, Christopher Bauman of the University of California, Irvine, Peter McGraw of the University of Colorado, Boulder, and others argue that the dilemma is too silly and unrealistic to be applicable to real-life moral problems. Therefore, they contend, it doesn't tell us as much about the human condition as we might hope.

In a survey of undergraduates, Bauman and McGraw found that 63 percent laughed "at least a little bit" in the fat-man scenario and 33 percent did so in the track-switching scenario. And that's an issue, because "humor may alter the decision-making processes people normally use to evaluate moral situations," they note. "A large body of research shows how positivity is less motivating than negativity."