Day two

Sierra Leone has its first-ever call centre. The number to reach it is 117. You can call to report that your mother is sick or your brother is dead. It is a call nobody wants to make, but posters and newspapers and radio broadcasts urge you to pick up the phone – for your own sake and your family’s, but beyond that, for the sake of everybody else you know and don’t know.

It’s a tough one, because that call leads to quarantined homes and holding centres for people with suspected Ebola, where people who do have the virus are sharing rooms with those who eventually turn out to have something else. There’s a real possibility you could go in with malaria and pick up Ebola. It is in the public interest that you make that call. But it is hardly surprising if some people hesitate and others run and hide.

In the offices of the British Council, which like so many other public buildings in Freetown has been commandeered in wartime fashion for the campaign against the deadly enemy within, is Victoria Parkinson of the Africa Governance Initiative, set up by Tony Blair. It has for some years been supplying advisers to the governments of six countries, including all three now devastated by Ebola – Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Parkinson advises the district Ebola response centre, or DERC, for the western area of greater Freetown, where the numbers of sick are climbing faster and higher than anywhere else in the country. In a large, light and airy room which looks as thought it should be full of pot plants, befitting a cultural embassy, teams of people take calls and dispatch ambulances to get the sick and burial teams to collect the bodies.

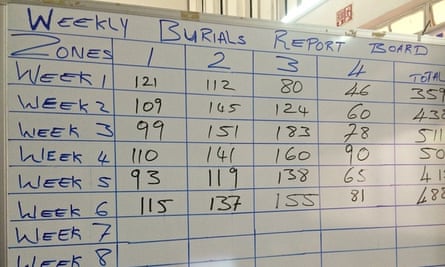

They send in surveillance officers to investigate homes where there have been deaths. They don’t get too close. “They do a clinical assessment from afar,” says Parkinson. It’s all run with military precision by the Sierra Leonean army. Grim scorecards on whiteboards are positioned around the room – the cases, the treatment beds available and the bodies.

“For the last five weeks we have buried every body reported to us the same day,” says Parkinson. “But yesterday we left 43 bodies because the burial teams had not been paid.”

It keeps happening. Sometimes it’s the burial teams, sometimes the nurses and sometimes the ambulance workers. All are supposed to get extra danger money. Nobody seems to know whether the government can’t pay, won’t pay or is just bureaucratically bogged down. Whichever, it causes deadly delays. Two weeks ago, burial teams dumped highly infectious bodies – local people claimed as many as 15 – in the street outside a hospital gate in Kenema in the east of the country to make their point.

Perched on the top of a hill overlooking the sea is another beautiful old building - the Prince of Wales school in Kingtom. All schools are closed under the president’s emergency decree forbidding public gatherings. Its playing fields have now been taken over by Médecins Sans Frontières, the volunteer doctors who were fighting the epidemic in west Africa and warning that it would be catastrophic for months before the World Health Organisation declared an emergency and triggered an international response.

MSF has great experience, having responded to every previous Ebola epidemic in Africa. They did not intend to start a treatment centre in Freetown, reasoning that they could leave the capital to others. They have changed their minds. And their answer to the fraught question of how quickly it is possible to put up a treatment centre lies in the white tented structures that have blossomed across the playing field. A tailor in a small tent that will become the nursing station is still sewing fabric to make the ceiling of the confirmed cases ward, but almost everything is ready. In 14 days.

The UK’ s Department for International Development, which is heavily involved in Sierra Leone, funding six treatment centres and much else, emails: “Just had end-of-day update from western area DERC - 106 bodies were buried today including 43 from yesterday - making up for last night, so zero reported bodies in the community tonight.”

So the command and control centre is back in super-efficiency mode. Everything they know about, they do something about. No more bodies in the streets. But nobody can explain why the number of reported deaths in Sierra Leone is 1,660 when the number of cases is 7,635. At best, the treatment centres send about half their patients out alive. It has to mean there are a lot of unreported deaths. I ask Rupert Simons, also from the Africa Governance Initiative, who is advising the national Ebola response centre whether he can explain the discrepancy.

“Ebola is a hidden killer. You can’t count it until people are infected with symptoms, by which time they have infected other people. So cases will be under-reported.

“There is a second fact compounding this. People are afraid to report their numbers to the government. They are afraid to call the helpline. They are afraid they will be taken away to treatment centres and never see their families again. There are reports of people disappearing into the forest because they’d rather die with their family than be taken into a treatment site.”

Yet Sierra Leoneans do now believe Ebola exists, he says, and they are better at compliance with public health advice than people in the UK, some of whom refuse to vaccinate their children.

I ask again about the low numbers for deaths. “It is a puzzle. We don’t know what it is. It is not a low death rate. It is probably the labs aren’t able to get swabs for all the dead bodies,” he says. That means they can’t be sure Ebola was the cause of death.

And there are many hidden deaths. “We have evidence that less than two-thirds of burials are being reported,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion