Mr. Eko, the Nigerian drug lord turned priest, would say that the story of Lost’s creation was not coincidence, but fate.

Hatched as a half-baked kernel of an idea by an ABC executive on his way out the door, the show became a gargantuan worldwide success just a few months later. The timing was fortuitous. Lost debuted just as social media was entering adulthood, and the show became the quintessential 21st century viewing experience. The “perfect storm of Lost,” as TV critic Alan Sepinwall puts it in his book The Revolution Was Televised, began on September 22, 2004. Ten years later, it really does seem like fate.

When Lost began, Facebook was in its infancy and Twitter was still two years away. But it was clear the current was changing. Lost fans had multiple ways to discuss the show: a barrage of forums and fan sites, its own rabidly detailed wiki Lostpedia, and a host of IRC channels in which fans would congregate on episode nights to discuss the show in real-time.

Fans also had many different ways to watch the show itself: live TV (the preferred option for those who wished to avoid spoilers), DVRs, DVDs, ABC.com (which, in 2007, started making episodes available for free the day after they aired), and Hulu. Hardware was changing, too: High-definition televisions increased in popularity while Lost was on the air. The sharp picture quality was perfect for taking advantage of the enchanting optics produced by the Hawaiian locales where the show exclusively filmed.

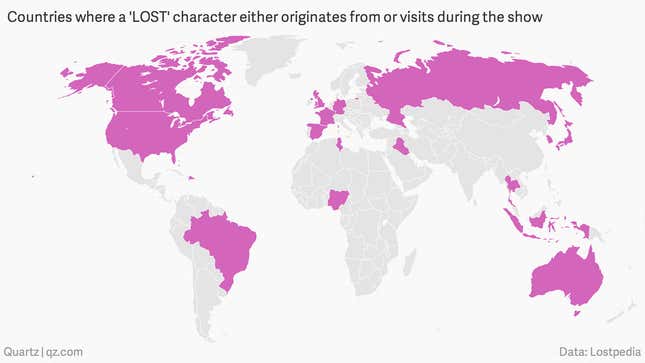

For a show about people stranded on an island, it sure managed to visit tons of countries (via flashbacks and, later, flash-forwards). The main cast featured an Australian, a Korean couple, a former Iraqi soldier, and two Brits (one English and one Scottish), as well as a throng of minor characters from other places like Brazil, Japan, and the Canary Islands. And many of its American characters, like everyman Hurley, were bilingual. The survivors of Oceanic Flight 815 were, by all accounts, what you might actually find on a trans-Pacific flight from Sydney to Los Angeles.

Perhaps as a result, Lost attracted a truly global fan base. The $14 million pilot attracted 18.6 million viewers in the US and 6.75 million when it debuted in the UK in 2005. In 2006, it was named the second most popular show in the world, after the CBS powerhouse CSI: Miami.

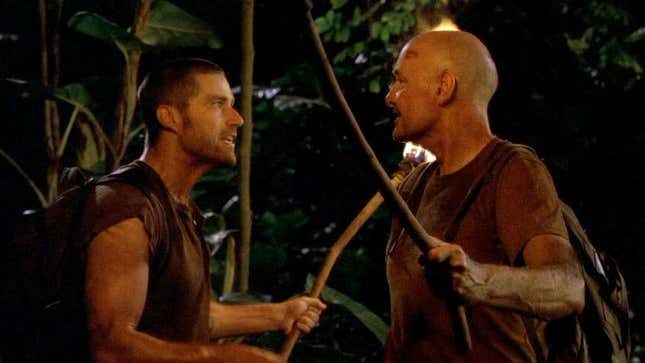

The show’s complex plot and cavernous mythology made it ideal for those fans from all over the world to investigate together and write about on the internet. In the Lost chapter of The Revolution Was Televised, Sepinwall writes that the show “didn’t invent internet discussion of TV shows…but it may have perfected the art.” Lost not only encouraged recapping, reviewing, and theorizing—it required it. Everything that came after an episode aired—the numerous crackpot fan theories, the Easter egg hunting, the frame-by-frame analysis of crucial scenes, the alternative reality games—were every bit as crucial to the Lost experience as watching the show was. “There was this unforeseen confluence of events where we were making a show that was perfect for discussion and debate, just at the moment where the internet was evolving into a place where people were forming communities where they could have those discussions and debates,” Carlton Cuse, one half of the Lost showrunning duo, told Sepinwall.

Another way fans interacted with the show were podcasts, like the popular Lost Podcast with Jay and Jack, which created mini celebrities out of the father-son duo within the Lost community. But the majority of discussion took place on forums, and each one was its own unique community within the larger ecosystem of the show. DarkUFO was known for posting scoops and spoilers and hosting an IRC channel. Lostpedia, of course, operated the Lost wikipedia, but also had its own IRC channel (though that eventually folded into the DarkUFO IRC channel, due to some Lost online community drama—yes, that existed). And then there was The Fuselage, a message board sponsored by J.J. Abrams himself, which frequently held Q&As with the cast and crew. It was an extremely direct line of communication between the stars and their fans. In that sense, it was Twitter before Twitter.

Most of these communities were fan-driven, but many journalists (Sepinwall included) helped lend an air of legitimacy to the eccentricities of the average Lost fan. Chief among these writers was Jeff “Doc” Jensen, a writer for Entertainment Weekly whose zany, masterfully-constructed recaps were required weekly reading for Losties. As talented a writer Jensen was, he was a Lost fanatic at heart, which made him no different than the people reading his columns. Never before Lost were TV recappers such an integral part of the experience of the show they wrote about—and probably not since, either. The merits of TV recapping have been debated ceaselessly by writers in recent years, but there’s no debating that recaps and Lost were a match made in heaven.

Sure, there were downsides to the experience of the show pervading all corners of the internet. First, people were getting spoiled. Unless you watched the episode live as it aired, it was next to impossible to stay spoiler-free lest you avoid the internet altogether. Lost didn’t end when an episode cut to black—in fact, it never really ended. It was an open-ended question, a math problem with no solution. It was a constant. There was no way to watch the show and not be a part of that global community, whether wittingly or not.

Social media gave a powerful voice to Lost‘s critics, and the people making the show heard them. Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse made themselves absurdly accessible to fans, hosting weekly (hilarious) podcasts, attending Comic-Con with the cast every year, and agreeing to countless interviews with reporters. For better or worse, Lost made both of them famous. Fans needed answers, they needed reassurance that the show had a plan, so “Darlton” (as they’d become colloquially known) hoped their presence online would assuage skeptics’ fears. It worked while the show was on the air, but now that it’s over, it’s left the duo—mostly Lindelof—as the punching bag for angry ex-fans who thought the ending cheated them out of six years of their lives.

Normally, that would be an odd argument. But Lost, more than any other show before or since, was a vast emotional and intellectual investment. People actually put their lives into it. People were hurt when the ending didn’t live up to their impossible expectations. (I am not one of them: I thought the ending was good, not great, but what mattered more to me was the six years of captivating storytelling.) A vocal minority of Lost fans thought that the ending ruined the show completely, and they made sure Lindelof, who was very active on Twitter, knew about their disdain. Lindelof shook off the backlash for awhile, but eventually quit Twitter because of it.

It’s unfortunate that the improbable story of Lost had to end that way. But you could feel it coming. For me, it was somewhere around the middle of season three when I realized that they could not possibly finish this thing without disappointing some people. For as rabid as the fan base was during the show, they would be even more rabid in their anger once it ended. It was doomed to frustrate people from the very beginning. For many, six fun years of theorizing and discussing and podcasting became instantly irrelevant when the show didn’t finish as perfectly as the imaginary ending they had in their heads.

And maybe that will be the ultimate legacy of the show. Maybe, in 30 years, people will think of Lost as that show that was cool for a long time but wound up having a terrible ending. But I won’t. Ten years since the pilot, it’s clear to me that Lost cemented itself in the TV pantheon as the show with the most involving, entertaining, community-like experience. Lost was the show that made you want to feel a part of something, and a lot of that was because of how incredible its timing was during an era of remarkable technological innovation. If it happened a few years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have been nearly as big of a hit.

There were global shows before Lost, and there were community-driven shows before Lost, but there were no shows with truly global communities before Lost. Game of Thrones is doing something similar today, but there really are no apt comparisons. There will never be another Lost. For that reason alone—the ending notwithstanding—it will be remembered.