The dinner invitations that dropped into the inboxes of political donors last week proudly boasted a list of guests whose names have already become very familiar in the crowded race for the Republican presidential nomination.

Jeb Bush, Scott Walker and Rick Santorum are among nine confirmed speakers for the Iowa Republican party’s annual Lincoln dinner in Des Moines. Rand Paul, Chris Christie and Marco Rubio have also been invited to an event that bills itself as a “star-studded” chance to meet the “top presidential candidates”.

“This dinner is an opportunity for our distinguished guests to set themselves apart and announce to Iowa and the country why they should be the next president of the United States,” wrote the state’s party chairman, Jeff Kaufmann.

By the time the dinner rolls around in May, many, if not all, of these names are indeed likely to have declared themselves either to be candidates or at least formally “testing the waters” for a run at the White House. Once they do, they are bound by strict rules governing how they can raise funds and what they must declare.

But at the time of mailing, only one of the invited speakers – Texas senator Ted Cruz – had triggered the start of his campaign by making such a legal declaration. Though many of the rest are poised to formally enter the race within a matter of days, there is mounting scrutiny of behaviour that some claim looks suspiciously like that of candidates but without the requisite checks and balances.

To much of Washington’s political and media class, the ambiguity is merely part of the game: something to tip-toe through carefully with the help of highly paid lawyers.

Nearly all of the widely accepted list of politicians thought to be running in 2016 have formed some sort of fundraising organisation – a leadership PAC, a super PAC or even politically active nonprofits. While simultaneously denying the existence of a presidential bid – or even a consideration of a bid – these non-candidates are traveling the country, raising cash and setting up field operations in early primary states. All of those things are exactly the type of activity that is usually disclosed publicly to regulators but which remains off the books for now.

Yet anger is building among transparency campaigners, some of whom are expected to soon launch a legal challenge with the Federal Election Commission (FEC), arguing that some of the biggest names in American politics have been actively flouting the rules.

“The big issue, and the one that is repeatedly being misreported in the press, is the question of when the candidate contribution limits kick in,” said Paul S Ryan, senior counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonprofit advocacy group founded by former John McCain lawyer Trevor Potter.

“I’ve seen a lot of incorrect reporting saying that they’re all saying they’re not candidates, because that way they don’t have to comply with contribution limits,” Ryan explained. “That’s not true. Contribution limits kick in as soon as you start raising and spending any money to start ‘testing the water’ to determine if you’ll run.

“The simple denial – ‘Oh, I’m not a candidate’ – that doesn’t get you out of the contribution limits. The only way to get out of the contribution limits is to say ‘I’m not even testing the waters’.”

Freudian slips – or a laughing matter?

A joint analysis by the Guardian and the Center for Responsive Politics has found multiple instances where politicians do appear to have sailed dangerously close to the definitions used by regulators.

Whether these are certain breaches of the rules about declaring a candidacy is open to debate, but there is plenty of nervous legal backpedaling.

“I’m the only candidate who thinks that the NSA program on bulk collection of your phone records should be shut down,” boasted Kentucky senator Rand Paul during a recent session at the South By Southwest technology conference in Austin, Texas.

After the reference to his candidacy was questioned online, a follow-up tweet hastily said Paul was talking about his status as a candidate for Kentucky senate election – though without explaining why he was campaigning for this race hundreds of miles away in Texas.

Others try to laugh off any such Freudian slips.

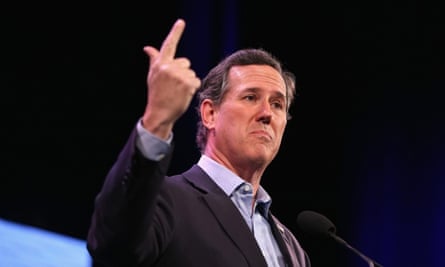

“I remember the last campaign,” reminisced Rick Santorum, who also ran in 2012, during one of several recent trips to Iowa. “Well, not that we’re in a campaign,” he added quickly, according to the Des Moines Register, which reported that the audience laughed as Santorum quipped: “The FEC is watching!”

This nodding and winking with the audience is a particularly commonplace feature of Jeb Bush’s many appearances on the national stage and in early-voting states such as Iowa and New Hampshire.

The former Florida governor rather cryptically declared last December that he had “decided to actively explore the possibility of running for President of the United States”. By the time he appeared at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Washington in February, he was happy to explain why.

“If I go beyond the consideration of the possibility of running, which is the legal terminology that many of the people here coming to CPAC are probably using to not trigger a campaign …” Bush began.

During a recent session with business leaders in New Hampshire, he acknowledged: “I get really nervous about not triggering a campaign with all of these people around.”

“I’m considering the possibility of running,” he corrected a questioner who suggested he already was.

‘A lot of verbal gymnastics’

Under FEC rules, what other people – even party chairmen in Iowa – chose to call candidates is less relevant than how they refer to themselves and how they actually behave. But sometimes it is the circumstantial evidence that seems most damning.

Wisconsin governor Scott Walker also came to CPAC, claiming: “If we can do it in Wisconsin, there is no doubt we can do it across America.”

In New Hampshire more recently, the Associated Press even reported that he said his sons were preparing to skip college this autumn to join him on the campaign trail.

“They twisted our arms to figure out a way to maybe take part of a semester off next year, next fall, to come to New Hampshire, to come around the country and talk to young people like themselves,” admitted Walker.

To those on the inside, these are mere slips of the tongue, rather than anything that meaningfully clashes with carefully planned timetables for declaring later in the year.

“The governor is not a candidate at this time,” Walker’s spokeswoman, AshLee Strong, flatly told the Guardian when asked about his sons skipping school to campaign for him.

“Through Our American Revival, the governor is talking about his issues platform based on the big, bold reforms he was able to achieve in Wisconsin as model for the rest of the country,” Strong added. “He will continue to advocate for these types of reforms as he travels throughout the country.”

Others, including spokespeople for Paul, Bush and Santorum, did not respond to requests for comment – a silence that critics claim is designed to avoid spelling out exactly what their status is.

“We see a lot of verbal gymnastics by these candidates at public events,” said Paul S Ryan at the Campaign Legal Center. “Yes, they often mention that their lawyers make them say they’re thinking about being candidates, but the simple fact that your lawyers made you say something and you say it doesn’t immunise it.”

For the purists, any evidence that you have made your mind up to run should be enough to trigger the disclosure requirements.

“The fact that they are willing to lie or joke about it in public doesn’t change what the law is,” Ryan added. “You cannot get around legal candidates status by lying. If you have decided to be a candidate, making a joke out of it doesn’t mean you haven’t decided.”

Raising money or raising visibility?

The verbal clues to a candidacy are compounded by dozens of trips made by the frontrunners to Iowa and New Hampshire, something that critics believe goes way beyond simply helping candidates make up their mind.

Local political experts, however, take a more sympathetic view of such trips, arguing that it does not matter to voters if all their high-profile visitors are not officially candidates just yet.

Dante Scala of the University of New Hampshire said such visits were less about raising money than about raising visibility among the party activists who will decide who gets a shot at the real primary.

“Yes, there are some donors in New Hampshire, but they don’t hold a candle to places like New York or California,” Scala said. “So this is all about votes and winning and getting that early boost of momentum and so forth.

“Sure, activists are interested in how much the candidate can raise, but not how much they can raise here.”

Even the politicians’ harshest critics concede there is little chance of being able to inflict meaningful punishment on phoney primary candidates, preferring instead to see any FEC appeal as a symbolic attempt to draw attention to how broken the system is.

“They can make it because the FEC is such a feckless enforcement agency,” said Ryan. “No one fears it. They know that even if the FEC does something, it will come along well after the election and it will amount to a slap on the wrist.

“So the question becomes: would you rather be a president, and two or three years after the fact be asked by the FEC – not told, asked – to pay some fairly trivial fine, or not be a president ever? That’s the calculation.”

- Russ Choma is a reporter for the Center for Responsive Politics

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion