A heap of Anglo-Saxon coins glittering as if newly minted, and a small gold cross still containing a fragment of a relic that was literally kept close to the heart of somebody who clung to the outlawed Roman Catholic faith, are among the treasures found by metal detectors and unveiled this week at the British Museum.

The most recent year covered by the Treasure report, 2012, was another bumper year for precious objects – including 3,000-year-old golden bracelets belonging to a child, a Viking hoard of ingots and chopped up arm rings from Cumbria – and for the more modest but historically priceless archaeological objects voluntarily reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS).

However, the internationally admired system for recording treasure is itself under threat from central and local authority budget cuts.

The mapping of the two schemes has unlocked a wealth of new information, identifying thousands of previously unknown sites including bronze-age burial grounds, Roman campsites and Viking settlements.

In 2014, 113,962 finds were reported, from scraps of horse harness to lost buttons, and well over 1m objects have been recorded since the PAS was established in 1997.

The Treasure and Portable Antiquity schemes are run together from the British Museum, with the finds recorded by a network of archaeologists based in local museums covering England and Wales.

However, the PAS has been hit by a 6% budget cut at the British Museum, and has only been kept going for the next year by an emergency grant from the private Headley Trust charity. Almost a third of the 31 local authority museum partners have said they will not be able to afford to keep the scheme going if their funding is cut further.

Neil McGregor, the director of the British Museum, said he could give no guarantees that the scheme would be protected from the full impact of future cuts in his museum grant. He said: “The PAS is an integral part of the British Museum, and we will just have to see what happens.”

Cuts already being implemented are reducing the number of outside events, including finds days and metal-detecting rallies. This could affect the reporting of both small and major finds – such as the Anglo-Saxon hoard discovered a few days before Christmas by detectorist Paul Coleman.

A local finds officer had gone to the metal-detecting rally on farmland in Lenborough, Buckinghamshire, and was there to help lift the thousands of coins and recover every scrap of context information.

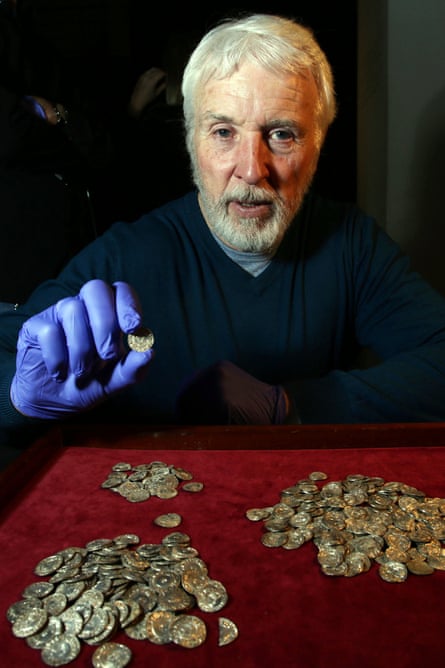

“It was like doing the lottery for years. You’ve spent so much time on it and then you know you’re finally going to have something big to show for it,” Coleman said of the moment when he saw the coins glinting in the mud at the bottom of a 2ft-deep hole in a field.

A single Roman denarius was his next best find in 40 years out in all weathers with his metal detector: the 5,200 Anglo-Saxon silver pennies and ha’pennies, from 40 different mints, so giving a unique insight into how money was circulating in Britain 1,000 years ago, are of national importance.

On 21 December, he was reluctantly persuaded by his son Liam and a friend to travel 120 miles from their homes in Southampton to join a metal-detecting outing expected to be more of a Christmas jolly than a treasure hunt.

After an hour they had found one musket ball, and decided to move on – but were detecting their way up towards the gate at the top of the field when Coleman asked his friend to move to stop interfering with his signal, was brusquely told to shove over himself – and immediately came upon the hoard.

Because museums and archaeology units were already closing for Christmas, they decided to remove all of the coins themselves for safe keeping, and when their Sainsbury’s carrier bag began to disintegrate, had to borrow another plastic bag from the farmer.

The hoard had been wrapped in a lead sheet, which was heavily corroded. When it came to conservator Pippa Pearce at the British Museum in a vintage McVitie’s biscuit tin, she described the lead as looking like “a roadkill Cornish pastie”.

It had, however, done a magnificent job of protecting the coins for 1,000 years: most came up glittering after a gentle application of toothbrush and soapy water.

The Anglo-Saxon coins, which the county museum in Buckinghamshire hopes to acquire with the help of the British Museum, are still going through the treasure valuation system, but the reward to be shared by Coleman and the landowner could be up to £1m.

“It’s customary to do right by the people who were there with you to help,” Coleman’s son said pointedly.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion