Story highlights

NEW: "Emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria presents a formidable challenge," a manufacturer says

UCLA officials say deadly bacteria was "embedded" on scopes even after cleaning guidelines were met

UCLA hospital is now using an additional cleaning procedure of applying gas to endoscopes

The superbug CRE outbreak connected to two patient deaths at a UCLA hospital was caused by two medical scopes that still carried the deadly bacteria even after disinfection guidelines were followed, hospital officials said Thursday.

That finding highlighted a U.S. Food and Drug Administration safety communication issued earlier in the day about how the complex design of the endoscopes “causes challenges for cleaning and high-level disinfection.”

That FDA advisory was designed to raise awareness among health care professionals.

The UCLA hospital was using a duodenoscope made by Olympus, but the Food and Drug Administration is also reviewing data from the two other U.S. companies that make the devices, Fujifilm and Pentax.

Pentax Medical said in a statement that it is working with the FDA and medical professionals to uncover any possible vulnerabilities in its device’s design or sterilization procedures.

Duodenoscopes are most commonly used to do procedures on the gallbladder, pancreatic ducts, and the bile ducts, which are a series of thin tubes that reach from the liver to the small intestine.

An internal review at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center found that the cleaning protocols set by the FDA and scope manufacturers still didn’t remove the superbug from the devices.

In fact, the superbug was “embedded” in the scopes even after cleaning, said Dr. Robert Cherry, chief medical and quality officer of the UCLA Health System.

Since that internal January 28 finding, the hospital is now using an additional new sterilization procedure that involves applying a gas to the scopes, hospital officials told reporters.

“There’s no risk,” Cherry added.

Changing national discussion

The hospital review found no deficiencies in its cleaning process of the scopes, said Dr. Zachary Rubin, medical director of clinical epidemiology and infection prevention at the UCLA hospital.

That internal review suggests “that the routine processes we were using just weren’t adequate,” Rubin said.

Dr. Benjamin Schwartz, deputy chief at Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, said the complexities of the scopes save lives, but he added: “They are very, very difficult to clean. The FDA recommendations were followed by UCLA.”

In all, seven hospital patients were infected with the deadly superbug between October and January, including the two who died, officials said. The medical center has contacted 179 others who had endoscopic procedures between October and January and is offering them home tests to screen for the bacteria.

At a press conference, Rubin acknowledged Thursday’s FDA safety communication and the scope manufacturers, but he added, “we’re not part of the process” of communication between those two parties.

The UCLA case is now having national repercussions, said Dr. David Feinberg, CEO of UCLA’s hospitals.

“What we have done at UCLA today has already changed the discussion nationally about these scopes,” Feinberg told reporters. “When something like this happens, it really gets us in our gut.”

Manufacturers respond

Olympus Corp., one of three scope manufacturers identified by the FDA, said it provides instructions, guidance and supplemental educational materials on how to conduct effective cleaning of its endoscopes, also called duodenoscopes.

“While all endoscopes, including duodenoscopes, require thorough reprocessing after patient use in order to be safe, the Olympus TJF-Q180V requires careful attention to cleaning and reprocessing steps, including meticulous manual cleaning, to ensure effective reprocessing,” which is a reuse of the same device, said Mark A. Miller, the company’s executive director of communications and marketing.

In addition to instructions and guidance given to every customer, Olympus makes available supplemental educational materials on cleaning the devices, Miller said.

“Olympus is monitoring this issue closely including today’s safety communication from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). We are working with the FDA, relevant medical societies and our customers regarding these concerns,” Miller said.

Another manufacturer, Fujifilm Medical Systems USA Inc., is working with the FDA “to evaluate and respond to concerns regarding the possible association of certain reprocessed endoscopes, specifically a feature of duodenoscopes, with disease transmission,” a company statement said Thursday.

“Like the FDA, we are continuing our evaluation and closely monitoring. Fujifilm is dedicated to protecting the health and safety of patients, and will continue to do so,” the firm said.

The third manufacturer, Pentax Medical, is working with the FDA and industry partners “in analyzing the recently publicized CRE incidents and uncovering potential vulnerabilities in duodenoscope design and reprocessing methodologies,” the firm said.

“The emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria presents a formidable challenge to the entire health care community,” a Pentax statement said. “As is the case for many other types of endoscopic procedures, the rate of infection for ERCP remains extremely low, and the benefits of the procedure far outweigh the risk.”

The seven patients at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center caught CRE after routine endoscopic treatments for bile ducts, gall bladder or pancreas, a hospital spokeswoman said.

The outbreak originated when one patient – which medical circles call a “source case” – had CRE before a scope procedure at the hospital, Cherry said.

Then other patients became infected with CRE after their scope procedures at the UCLA hospital, Cherry said.

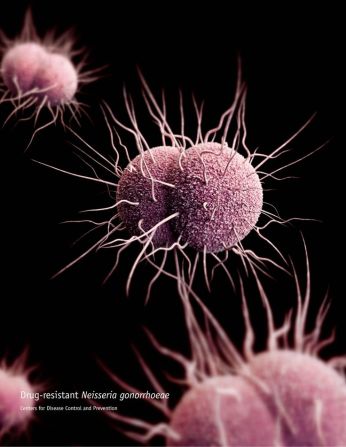

CRE is short for carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae, and it was a contributing factor in the deaths of two of the seven patients, a hospital spokeswoman said.

But the exact cause of those deaths wasn’t immediately disclosed, according to hospital officials.

“This particular bacteria can actually create an enzyme that essentially inactivates antibiotics. It’s got a defense mechanism that is evolved into it, so it’s a really smart yet frightening bacteria,” said CNN’s chief medical correspondent, Dr. Sanjay Gupta. “This is an example of antibiotic resistance and the consequences of it.”

One patient’s account

One of the seven patients blamed one manufacturer of the medical scope, Olympus, for his infection, the patient’s attorney said Thursday.

The accusation was made on the same day the FDA issued the advisory about how the scope’s design may impede effective cleaning.

The patient, an 18-year-old high school student whose name wasn’t released, is planning to sue Olympus, said attorney Kevin Boyle.

The student was “very, very close to death” and is back in the hospital, Boyle said. “He’s not doing well now.”

An Olympus spokesman couldn’t be immediately reached to respond to the attorney’s accusation.

The patient initially went to the UCLA hospital for a suspected leaking pancreas in 2014, Boyle said.

But the outpatient endoscopic procedure didn’t reveal a leaking pancreas, and the youth returned home, Boyle said.

Later, the young man was taken to a hospital again, where he remained for more than 80 days, Boyle said. The patient also spent time in intensive care, Boyle added. The attorney declined to state whether the second hospital visit was at the same UCLA facility.

The attorney also said Thursday the patient doesn’t blame the UCLA hospital for his infection.

The patient was released from hospitalization, but within the last two weeks, he returned a third time to a hospital, where he remains, Boyle said Thursday. The attorney also declined to identify that hospital.

Boyle alleges that in mid-2014, Olympus altered the design of the endoscope and removed a cleaning channel but didn’t change the cleaning protocol.

The procedure and its scopes

The scoping procedure is called endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or ERCP, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy said.

The medical procedure is used to, among other things, unblock bile ducts and take care of pancreas issues.

“It is estimated that more than 500,000 ERCPs are performed each year in the U.S.,” the society said. “From what we know, over the past few years, there have been fewer than 100 known cases of transmission of these problematic bacteria through ERCP.”

The ERCP procedure involves a duodenoscope, a flexible, lighted tube that is threaded through the mouth, throat, stomach and into the top of the small intestine (the duodenum), the FDA said.

The device contains a hollow channel that allows the injection of contrast dye or the insertion of other instruments to obtain tissue samples for biopsy or treat certain abnormalities. The device also has a movable “elevator” mechanism at the tip, the agency said.

Even meticulously cleaning the devices before high-level disinfection “may not entirely eliminate” the risk of transmitting infection, the FDA said.

“Reprocessing is a detailed, multistep process to clean and disinfect or sterilize reusable devices. Recent medical publications and adverse event reports associate multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients who have undergone ERCP with reprocessed duodenoscopes, even when manufacturer reprocessing instructions are followed correctly,” the FDA said.

“Although the complex design of duodenoscopes improves the efficiency and effectiveness of ERCP, it causes challenges for cleaning and high-level disinfection. Some parts of the scopes may be extremely difficult to access and effective cleaning of all areas of the duodenoscope may not be possible,” the FDA said.

CNN’s Debra Goldschmidt and John Bonifield contributed to this report.