“So, what kind of music do you like?” It’s one of the hardest questions to answer in a social situation, especially as you get older and your tastes diversify.

Whenever I’m asked, I tend to end up mumbling a mish-mash of genres and artists. But here’s an alternative question: what kind of music does Spotify think I like? It should know, after all.

I’ve been using the streaming music service since it launched in 2008, and since about 2011 it’s been my main music player – including for songs and albums that I’ve bought from other sources like iTunes and Bandcamp during that time.

Spotify has my big music data, just like it does for all 50 million of its active users. In 2014, it bought a music technology company called The Echo Nest to help it make sense of all this data, and understand its listeners better.

So, does it understand me? I asked the company, which agreed to compile a report of my “taste profile” and talk me through it. A quick caveat: nobody should care about my individual tastes other than myself: this isn’t a look-how-cool-I-am show-off article.

However, drilling down to one individual is a useful step towards understanding how the algorithms developed by Spotify and any digital entertainment service worth its salt are making sense of our habits, in order to serve us better.

The basic data

Spotify’s product owner of taste profiles, Ajay Kalia, explains that my taste profile is based on music I listened to between 1 January 2013 and 19 December 2014 – Spotify has data before that period, but the taste profile algorithm hasn’t ingested it yet.

During that period, I listened to 7,328 individual songs by 2,140 artists on Spotify for 22,780 total “plays” – tracks listened to for at least 30 seconds. The base for anyone’s taste profile then comes from the songs and artists that they’ve listened to most.

Here are my most-played artists:

- Disclosure (675 plays, 68 songs)

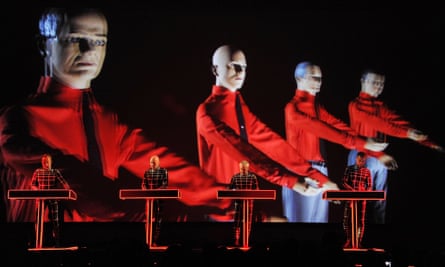

- Kraftwerk (463 plays, 68 songs)

- Deltron 3030 (378 plays, 44 songs)

- Hurray for the Riff Raff (373 plays, 48 songs)

- Jagwar Ma (367 plays, 26 songs)

- Courtney Barnett (307 plays, 33 songs)

- AlunaGeorge (292 plays, 29 songs)

- Laura Marling (283 plays, 54 songs)

- Haim (274 plays, 25 songs)

- Cate Le Bon (272 plays, 51 songs)

- Ron Sexsmith (251 plays, 74 songs)

- Katy B (227 plays, 32 songs)

And here are my most-played songs:

- Second Summer - YACHT (86 plays)

- Forever - Lindstrom & Prins Thomas Remix (80 plays)

- The Throw (Extended Version) - Jagwar Ma (65 plays)

- Snake Road - Ron Sexsmith (65 plays)

- Confess To Me - Disclosure - Disclosure (57 plays)

- F For You - Disclosure (57 plays)

- White Noise - Disclosure (57 plays)

- Line of Fire - Junip (56 plays)

- Big Love - Matthew E White (55 plays)

- Invisible - Annie (55 plays)

- Analyser - AlunaGeorge (55 plays)

- Exercise - Jagwar Ma (54 plays)

- Waking Dream - Bleeding Rainbow (54 plays)

- Like a Sundae - Black Moth Super Rainbow (51 plays)

- A + E feat. Kandaka Moore & Nikki Cislyn - Clean Bandit (50 plays)

- She Burns - Joe Goddard (50 plays)

- Don’t Save Me - Haim (48 plays)

- Pale Green Ghosts - John Grant (48 plays)

- It’s Alright, It’s OK - Primal Scream (48 plays)

- Fresh - Summer Camp (47 plays)

- Next Stop - Bleached (47 plays)

- When a Fire Starts to Burn - Disclosure (46 plays)

- Pay Us No MInd - The Staves (45 plays)

- Love is Only Affection - The Dig-Its (45 plays)

- Fire! - Steve Mason (44 plays)

“We start by trying to understand the songs you’ve been playing and how many times you’ve been playing them, then roll that up into the artist data too, to get a basic grounding of your tastes,” says Kalia, running me through the data.

There is more to a taste profile than that, though: my data is then mapped against wider “cultural knowledge” about how those artists are described online, and the characteristics of their music – The Echo Nest famously analyses songs using criteria including acousticness, organicness, tempo and even “danceability”.

My personal data can also be mapped against what the 50 million other Spotify users are playing, sharing and adding to playlists. After running all this through an internal Spotify tool called Nestify, Kalia comes up with a more visual representation of my music tastes, sorted by “cluster”.

Music clusters

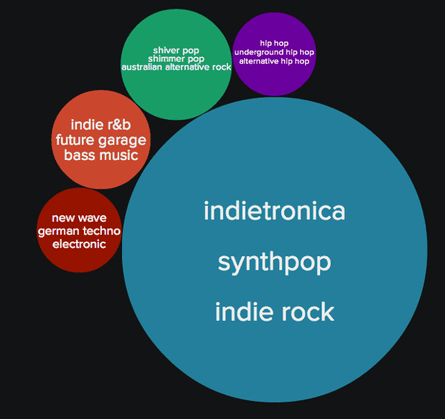

That’s the map of my tastes above, which certainly sounds cooler than anything I’d usually mumble to a stranger asking me at a party. Indietronica! Synthpop! Future Garage! And whatever Shiver Pop is when it’s at home!

If you use Spotify, it’ll have a similar version of this map for you buried in its system. Kalia explains it, saying that three of these bubbles are my “dominant” clusters of music listening, which his report outlines thus:

Cluster one: Indietronica, Synthpop, Indie Rock

Hurray for the Riff Raff, Laura Marling, Haim, Shit Robot, YACHT, Veronica Falls, Royal Blood, Kathryn Williams, Primal Scream, Cut Copy, Joe Goddard, The Asphodells, Janelle Monae, The Asteroids Galaxy Tour, Gruff Rhys, Jimi Goodwin, Lady Gaga, Taffy, Aphex Twin, Sophie Ellis-Bextor, Bleached, Hot Chip, Holy Ghost!, The Charlatans, Franz Ferdinand

Cluster two: Shiver Pop, Shimmer Pop, Australian Alternative Rock

Jagwar Ma, CHVRCHES, Deap Vally, Icona Pop, Outfit, Drenge, Young Wonder, Electric Guest, Satellite Stories, Marika Hackman, Daniel Avery, Thumpers, Palma Violets, Austra, Wolf Alice, The Child of Lov, Little Green Cars, Yus, The History of Apple Pie, Charli XCX, Willy Moon, The 1975, She Makes War, Public Service Broadcasting, Glass Animals

Cluster three: Indie R&B, Future Garage, Bass Music

Disclosure, Burial, James Blake, Bondax, Jamie XX, Sampha, Dark0, Gold Panda, Zomby, SBTRKT, Mount Kimbie, Blind Prophet, Scuba, Daphni, Ifan Dafydd, Julio Bashmore, Gorgon City, DCult, Shackleton, TCTS, Royce Rolls

There are two smaller clusters too: Kalia tells me that the New Wave / German Techno / Electronic cluster is dominated by Kraftwerk, while the Hip Hop / Underground Hip Hop / Alternative Hip Hop one is dominated by Deltron 3030, with a little input from Jurassic 5, The Roots and The Fugees.

What this means

Kalia adds more information on how Spotify is interpreting my listening data. “You are what I’d informally say is a power user: you’re playing music a lot, and a lot of different songs by a given artist, sampling and moving on or sampling and staying with it,” he says.

“While a lot of people might have 100 or 200 plays for a single song, you do seem to be more spread out in your listening. And most of your listening comes from a handful of playlists that you’ve made, which almost seemed to function like a collection.”

In fact, more than 50% of my listening in 2014 came from just two playlists that I’d created for exactly that purpose: Stuff To Listen To (a grab-bag of new releases and recommendations from friends, media reviews and radio-station playlists) and Stuff I Like (songs from that grab-bag that I enjoyed).

“It’s essentially a lean-forward collection or queue,” he says, before explaining why Spotify has decided that two of my artist clusters aren’t as dominant: the system knows that I spent a month or so listening heavily to Kraftwerk in 2013, but barely since.

Meanwhile, my hip-hop listening has zeroed in on a small number of artists: “You haven’t shown a propensity for that kind of music throughout Spotify,” as Kalia puts it.

In other words, Spotify’s algorithm thinks I’m more an individual fan of Kraftwerk and Deltron 3030 than I am of their respective genres: I may have played Hurray for the Riff Raff less than either, but it’s more reflective of my overall tastes.

Kalia explains that as music recommendation algorithms improve, they’ll regularly encounter challenges like this. Is someone streaming Michael Bublé lots in late December showing a propensity for crooners, or simply exhibiting the Christmas spirit? Is that user heavily playing the Frozen soundtrack a huge Disney fan, or the parent of a huge Disney fan?

These and many more questions are, I suspect, what makes the role of Kalia and his peers at rival streaming services one of the most fascinating jobs in the music industry right now. Their algorithms are trying to understand what we listen to, how and when we listen to it, and how that music relates to other music.

“There is a lot we’re still trying to understand about our listeners, even within the years and years of data that Spotify already has,” as he puts it. “All this goes towards understanding why you are opening Spotify right now, and what you might want to hear next.”

Better recommendations to come

The Echo Nest can already make recommendations on that score: for each of my clusters, Kalia provides me with three playlists tuned to those tastes: My Music (sticking to tracks and artists I like), Discovery (new songs and artists that I should like, based on this cluster) and Default (a middle ground between the two).

Here’s the Discovery playlist for my main cluster, as an example:

And here’s the one for my third cluster, if you’re in more of a future garagey indie R&B bass-musicy mood:

For now, the Nestify tool is for internal Spotify use only: you can’t go in and browse your own taste profile and demand the service whip up some playlists for you.

Kalia says the company is thinking hard about how some of these features could be surfaced: for example, the ability to ask someone how adventurous they’re feeling, then provide a playlist to match.

At a time when most streaming services cost more or less the same amount if you subscribe (£9.99/$9.99/€9.99) and have roughly the same catalogues, it may be this kind of personalisation that defines which companies are best at hanging on to their users. In Spotify’s case, it may be crucial as it prepares for a battle against much-richer rivals like Apple and Google.

What’s missing?

As interesting as the data above was, it doesn’t yet tell the full story about my music listening – or, at least, my historical music listening.

Spotify doesn’t know that the teenage me’s musical awakening came in the mid-1990s to Britpop; it doesn’t know about my subsequent journey through phases of big beat, pale young men with acoustic guitars, and hairy southern rawk.

It doesn’t know that I love the Black Crowes, the Chemical Brothers, the Charlatans, Primal Scream or the Super Furry Animals – my five touchstone bands but, it turns out, all artists I mainly play on CDs in the car nowadays, rather than through Spotify in other contexts.

(As a sidenote: I’ve been “scrobbling” to Last.fm from Spotify for a few years too, and my ‘most played artists’ page on that service has more of my listening from 2012, which brings some artists bubbling back to the top.)

Spotify doesn’t know that I really enjoyed Taylor Swift’s 1989 album in 2014, because having bought it – the album isn’t on Spotify – I mainly played it using the main Music app on iPhone. The same for Thom Yorke’s Tomorrow’s Modern Boxes, which through repeated (non-Spotify) listens became one of my favourite albums of the year.

These aren’t faults, as such: they just show why streaming taste profiles are still developing, and why there are likely to be a fair few gaps in their knowledge. And perhaps, also, a reminder that we don’t necessarily listen to the bands we “love” as much as we’d think.

Again, figuring out how to plug those gaps is one of the most interesting jobs in the digital music industry. One last thought, though: seeing my taste profile made me think about the distinctly un-rock’n’roll issue of data portability.

If, in 2015, I suddenly decided I wanted to jump ship to Beats Music, YouTube Music Key, Deezer or another streaming rival, could my taste profile go with me? Or would my new service be trying to learn my tastes all over again?

As more people realise the benefits of digital music services having a better understanding of our tastes, I suspect we’ll see more discussion about how (or even whether) we can export that data for use elsewhere.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion