Talk of Victorian asylums conjures up images of manacled and wretched patients suffering callous and ineffective treatments or being gawped at by a morbidly fascinated public like exhibits in a human zoo. However, a new project to digitise historical psychiatric records reveals an enormous range of care in the 18th and 19th centuries, including more genteel treatment for the upper and middle classes, as well as early developments in art therapy.

The Wellcome Library – part of the Wellcome Trust – is creating an online archive of more than 800,000 pages of documents from private and public asylums featuring doctors’ notes and patients’ artwork and writing.

It is working with other archives across the UK to provide fascinating detail of institutions’ efforts to improve the morals and morale of patients.

Lesley Hall, a senior archivist at the Wellcome Library, explains that there was a market in psychiatric care that mirrored the class system, from institutions that catered for the middle classes, such as the Camberwell House asylum, in south London, to the most exclusive, such as Ticehurst House hospital in Sussex.

“Ticehurst really was the lunatic asylum of choice for mad dukes,” she says. “It positioned itself in the market place to appeal to people who could afford quite high fees to make sure their insane relative is being cared for in very pleasant rural surroundings, in beautifully landscaped grounds and with a very high staff-patient ratio,” she says.

“Somewhere like Camberwell House asylum never really appealed to what you might call the carriage trade. They ended up in a kind of public-private arrangement with the local Poor Law authorities to take in pauper lunatics under a contract because there is no large local authority asylum in the area at that time.”

The York Retreat, founded by William Tuke and the Society of Friends (Quakers) in 1792, was one of the first institutions where people with mental health problems were treated humanely and with dignity. Katherine Webb, archivist at the Borthwick Institute for Archives in York, which holds the historical records on the retreat says: “The great difference between working‑class and middle-class care is that the families of potential middle‑class patients could choose what asylum they could send their relatives to. If you were working class you didn’t have that choice.”

The flip side of this was that the best private asylums could afford to be picky with the patients they accepted. Ticehurst, for example, avoided taking violent patients. However, the records show there was some unruly behaviour. Hall says: “I rather like the case of the Reverend Patterson who was a Church of England clergyman who behaved in a very un-reverend fashion. He threw a chair through a window, he expressed himself in violent and coarse language and he also groped the male servants. But that’s quite unusual. You don’t often get the sense they were sexually violent at the Ticehurst.”

Graham Roberts is archivist at Dumfries and Galloway Libraries, which keeps the records of Scotland’s grandest asylum, the Crichton Royal hospital, founded in Dumfries in 1838. He says the service patients received depended on how much their families paid. “You could pay up to £200-300 a year and be treated like one of the gentry or nobility – with your own room, your own servants and carriage rides every day,” he says. “In the case notes you get the impression sometimes that the patients think of the attendants as their servants rather than their superiors, even though they’re administering medicine to them and telling them what to do.”

Art therapy, often perceived as a modern development in psychiatric care, was in its infancy during the 19th century and Dr William Browne, the first medical superintendent of the Crichton, was one of its earliest pioneers. An insight into Crichton’s comforts can be found in the hospital’s magazine, New Moon, written, edited and printed by the patients. It included poetry, articles, reviews of hospital concerts and drama productions, cartoons, asylum news and puzzles. Roberts says: “From the pages of New Moon you would think the patients were having an absolute ball. They’re constantly talking about theatricals, visits they’ve had out to places, picnics they’ve been on, what they’ve been reading in the library, inspiration for their poetry that they’ve come across at the Crichton and what a wonderful place it is to be.”

According to the magazine, its intention was to “lead the inmates of the institution to think aright on the chief subjects that should occupy their attention under present circumstances. So that they leave it wiser and better men and women than they entered it”. As Robert puts it, there was a moral dimension to the magazine’s purpose.

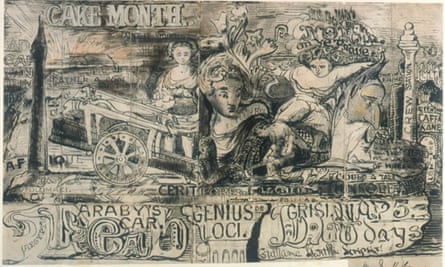

Other archival material evokes the troubled mental state of patients. For example, William Bartholomew – whose family set up their famous eponymous map publishing firm in Edinburgh – made a series of artworks that combine jumbled text and images. One called Cake Month features Nelson’s column next to an Egyptian style chariot and a couple of classical busts, and dotted around are a variety of words and phrases including “On ye brave” written above a cupid.

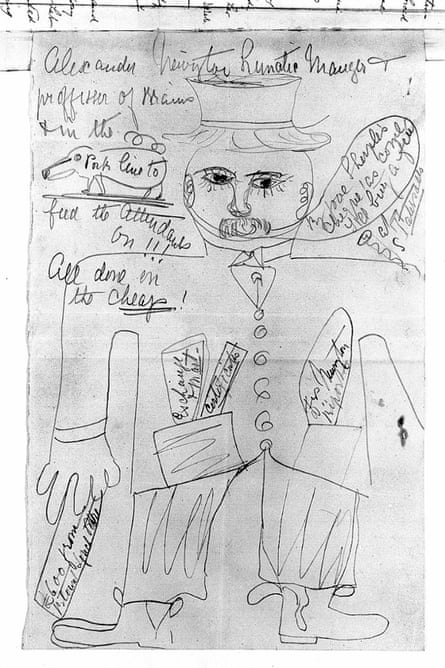

Other highlights of patients’ artwork in the digital archive include a shaky pencil drawing of a doctor at Ticehurst, stuck in the patient’s casenotes, and an oil painting by George Sidebottom, who was treated for moral and religious delusions at the York Retreat, depicting outdoor sports and recreation, which were considered beneficial to patients’ recovery.

One of the more amusing records of leisure activities at the asylums is a report called “Our Very Mixed Cricket” describing a match between the York Retreat’s men’s and women’s cricket teams. It details the players’ prowess, devoting much coverage to the female players’ range of talents. One extract notes: “A lady who I shall dub Stonewall Margaret was unmoveable. She adopted a style of her own. She entirely hid her wicket with her petticoats and their contents, till frightened by a rather fast and straight ball they fell. I was sorry because she was the life and soul of the business.”

This more personalised and humane approach was also reflected in the treatment of patients. Philippa Smith, principal archivist at the London Metropolitan Archives, says before St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics was founded in 1751 by philanthropists to make treatment accessible to poor people, their only provision was the Bethlem hospital, also known as Bedlam. It was here that the public were allowed to come and look at the lunatics on public holidays as a sort of entertainment. Smith says: “One of the first rules that St Luke’s established was that patients in the hospital were not to be exposed to public view – that lunatics were there to be cured and to be treated, not to be paraded as entertainment for people.”

St Luke’s ethos attracted the attention of social reformers; its records show visitors included Charles Dickens and prison reformer Elizabeth Fry. On his first visit in 1862, Dickens expressed some concerns about the conditions but when he returned six years later he was “much delighted with great improvements” and commended the “benign and wise spirit of the whole administration”. Fry, who visited the women’s wing of the asylum, commented on some “dirty patients” who wore no clothes, but also praised the “kind and judicious treatment of the lunatics”.

Dr Richard Aspin, head of research at the Wellcome Library, says the level of detail private asylums recorded about patients’ conditions and treatments, while a boon to historians, reflected just how closely patients’ every step was monitored.

Herman Merivale, a writer and playwright, who was admitted to Ticehurst two or three times, recounted his first evening in the asylum in his memoir My Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum, by a Sane Patient, published in 1879. The Ticehurst records reveal lengthy notes by his doctor on all aspects of Merivale’s life – from his mental state and sleeping habits to his food intake and bowel movements.

As Aspin explains: “The sense you got was of people being under constant surveillance. There was no hiding place. What you ate, when you went to the loo, what you did in your sleep – everything was documented. It’s very oppressive.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion