It’s a bitter cold morning in late January and pastor Gilford Monrose has forgotten his hat. Monrose is the president of the 67th Precinct Clergy Council, and he’s preparing to lead a crew of men and women of the cloth on an outreach mission to talk to East Flatbush residents about the central problem that plagues their neighborhood: its epidemic levels of gun violence.

The brightly colored “clergy response team” jackets issued by the city to the “God Squad”, as they are mostly known, were not designed for New York’s winter, but the team, which is made up of baptist ministers, episcopalian ministers, seventh day adventists and at least one rabbi, brave the cold regardless.

“There are too many young black men dying out here,” Monrose says in his rich Caribbean lilt, “and our work can’t stop because of the weather.”

Monrose co-founded the God Squad in 2010, after growing weary of encountering grieving parishioners who had lost a son or daughter to gun violence. Now a 60-member strong organization, it’s the largest and most active of six similar clergy councils that have sprung up around New York City, mostly in African American and Caribbean neighborhoods where tensions between the community and the police run high.

“Only in communities of color do you need liaisons between the cops and the locals,” Monrose explains, adding that it’s a role the church has been actively engaged in since the height of the civil rights movement.

Aside from acting as a buffer between the community and the police who serve them, the squad’s central mission is to eliminate gun violence. To this end, they organise outreach missions to engage with local youth; they respond to crime scenes to calm tensions in the aftermaths of shootings; they arrange emergency prayer vigils at hospitals; and they raise funds to pay for funerals of shooting victims whose families can’t afford to bury their dead.

“There’s an element of danger to the work at times,” says the soft-spoken reverend Donna Baptiste, one of the few female members of the squad. “But we have God on our side and if something happens, we know where we are going.”

The tension that exists between the police and mostly black communities gained national attention in recent months, following several police killings of unarmed black men and boys. The shooting death of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, led to over a month of rioting and protests. More anger ensued when 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot dead in Cleveland while playing with a toy gun in a park.

And in New York, the city erupted in protest following the failure to indict the white officer who strangled Staten Island native Eric Garner to death while he was being arrested for selling untaxed cigarettes. The incident, which was ruled a homicide by a medical examiner, was caught on camera and featured a desperate Garner gasping for air and repeating “I can’t breathe” several times.

“Every time these incidents happen, they make our work that bit more difficult,” Monrose says. “But we have to seize the moment and hope that out of chaos, order will come.”

As it is, the God Squad have plenty of local experience dealing with community anger over what they perceive as unnecessarily aggressive policing. For over a decade, the NYPD’s quota-driven policy, amped up under former commissioner Ray Kelly, saw hundreds of thousands of mostly young black men in high crime areas like East Flatbush being stopped, questioned and frisked by the police, often for reasons as vague as making “furtive movements”.

Then there were the shootings: in 2012, an unarmed 23-year-old African American woman, Shantel Davis was shot dead by NYPD officers in the 67th precinct while driving a stolen car. A year later, in the same neighborhood, 16-year-old Kimani Gray, a popular local boy, was also shot dead by police, who said the teen had pointed a gun at them (a claim disputed by witnesses).

Monrose learned of Gray’s shooting by text message in the middle of the night, and rushed immediately to the scene with other God Squad members, only to find a community up in arms. For several days, the clergy members worked tirelessly to calm the rioters. They took to the streets with bullhorns and prayer beads and, easily distinguishable in their yellow and orange jackets, were able to form a buffer of sorts between the grieving community and the police.

“The explosion of anger when another young black boy is killed by cops is very understandable,” Monrose says, “but the community also needs to look inwards and not lose sight of the fact we’re killing ourselves at even more alarming rates.”

For decades, East Flatbush has had one of the highest murder rates in the city. Last year, according to deputy police inspector Joseph Gulotta, who now heads up the 67th precinct, there were 63 shooting incidents involving 83 victims. The vast majority of these shooting incidents and most of the area’s murders do not involve the police.

Every week, a group of local mothers who have lost their sons to gun violence meet in the basement of Monrose’s church to help support and console one another as they work through their grief. As each of them takes turns recounting the story of their son’s deaths – 21-year-old Patrick Mondesir, shot dead by alleged gang members; 20-year-old Marlon Hinds, shot dead outside his mother Wendy’s apartment by alleged gang members; 14-year-old Akeal Christopher, shot in the head on his way to a high school party by alleged gang members – a complex picture emerges of a community being failed not just by the police but by elements within itself.

“Everybody is talking about the police shootings. Why can’t we address the real problem here which is us killing us!” says Akeal’s mother, Natasha Christopher, as she trembles with rage and grief over the memory of her young son’s murder. “It wasn’t the police that gunned down my child. It wasn’t the police who gunned down any of our sons, it was somebody black.”

“Black on black crime is a huge problem in the neighborhood,” said Gulotta during a meeting with the God Squad members in January. “It is also just a small group of individuals committing most of these crimes.” But bringing that small group to justice appears to be a problem.

Akeal Christopher’s murder has yet to be solved despite there being a host of witnesses at the scene. According to their respective mothers, the killers of Marlon Hinds and Patrick Mondesir are also still on the loose, a fact all the women attribute at least in part to a lack of concern by the police. “When your son is killed by alleged gang members, the police assume he was in a gang too,” says Christopher, as the other mothers nod in agreement.“They need to learn to not pass judgment on every black child and every black parent. I was not raising my son to be a gang member.”

But the mothers also acknowledge that the “code of the streets” plays a major role in allowing their sons’ killers to remain free. Pastor Monrose agrees. “In communities like East Flatbush a lot of people just won’t talk to the police,” he says. “It’s the idea of snitching.”

The other issue is that detectives in high crime neighborhoods like this one are overwhelmed by the work load. An investigation by the Daily News in 2013 found that there are thousands of unsolved murders in the outer boroughs of New York, with the 67th precinct topping the list with the highest rate of open cases. “This is where the lack of trust between the community and the police hurts everyone,” Monrose says, “and why maintaining a dialogue between the two is so important.” There are encouraging signs, he adds, that opportunities for these kinds of dialogue are increasing and that the tone is changing.

On 18 January, the eve of Martin Luther King Jr Day, Monrose and other God Squad members attended a Hope and Healing event for better police and community relations hosted by the Flatbush Seventh Day Adventist church. The event was also attended by a host of African American elected officials, including public advocate Letitia James and deputy police commissioner Benjamin Tucker.

Community members got the opportunity to offer condolences for the two NYPD officers, Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu, who were brutally murdered a few weeks prior, leading to a stand-off between the police union and New York City’s mayor, Bill de Blasio. But during the question-and-answer session some community members bore visible signs of frustration as they challenged the deputy commissioner over racial profiling and police brutality toward African Americans.

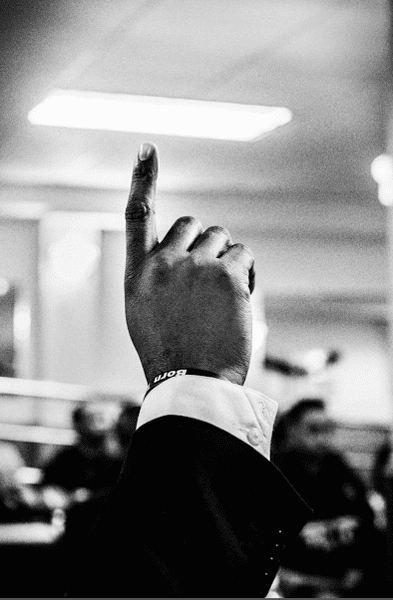

“Are you really telling me as a black man that I have nothing to fear in an encounter with a cop?” one audience member asked. Another African American woman rose to her feet and demanded to know why the police couldn’t just “shoot to stop” instead of always “shooting to kill”, especially when the target is a black man.

Tucker acknowledged that mistakes have been made. He also pointed out that with 35,000 active officers in the city, use-of-force incidents are relatively rare, at least in comparison to other police departments. But most of the discussion was focused on making needed reforms, some of which Tucker says are well under way.

He introduced a new community partnership program, which will seek to have neighborhood volunteers host new officers and make them part of the community when they start their job. He also spoke of a mentoring program, already up and running, that partners rookie graduates from the police academy with veteran officers when they first go out on the streets. And a state-of-the-art training academy, soon to be opened in Queens, will offer young officers sophisticated instructions in the appropriate use of force.

After the event, Monrose says he was “cautiously encouraged”. “More and more, I think the policy makers are getting it,” he said as he wrapped up warm before heading out into the winter night.

But the test will be how things play out on the streets. “When the average young black man in East Flatbush, East New York and Brownsville say they see a change, then we’ll know things have changed. We all have a lot of work to do to get there.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion