Why U.S. Colleges Should Welcome Undocumented Immigrants

Large numbers of them are pursuing fields that could greatly stimulate the country's economy.

As an undocumented immigrant who moved to California from Mexico as a child, Bianca Rodriguez expected that navigating college would be a challenge, both financially and emotionally. So it was the presence of the Undocumented Student Program that drew Rodriguez to the University of California, Berkeley, where she is now a sophomore.

The 19-year-old has found the resource center for students who are not in the U.S. legally so helpful that she has become an academic counselor there. "If I know I have a place where I feel like nobody will judge me," Rodriguez said, "it becomes easier for me to not only focus on school, but I know I have that support."

As a high-achieving young undocumented immigrant daunted by the challenges of higher education, Rodriguez is far from alone, according to a new report out of the Institute for Immigration, Globalization, & Education at the University of California, Los Angeles.

On top of the issue of paying for college—often without in-state tuition or financial aid—and the stress of illegal status, undocumented undergraduates in the U.S. also find themselves wondering whether a college campus is "undocufriendly." In other words, is it welcoming to students who are not in the country legally?

Undocumented Students' Priorities in College Selection

The report surveyed about 900 undergraduates throughout the U.S. who identified themselves as undocumented. The students came from 55 countries and attended schools in 34 states. They had lived in America for an average of 14.8 years.

About two-thirds of the students surveyed could pursue their education with protection from deportation through a program President Barack Obama announced in 2012—Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). The policy temporarily protects undocumented young people who meet its criteria from deportation, allowing them to work and get driver’s licenses. In November, Obama announced an expansion of the program by executive action, a move that Republican House Speaker John Boehner said this week he would challenge in court.

But as the UCLA institute and those behind the UndocuScholars Project, which put out the report, argue, these undocumented, high-achieving young people are students whose talents are worth nurturing.

"We’re finding that students are majoring in fields that are of great need to the nation," said Robert Teranishi, an education professor at UCLA and co-author of the study. Of the students surveyed, about 28 percent were majoring science, technology, engineering, or math (STEM) fields, an area that is arguably suffering from a shortage of qualified candidates in the U.S. That’s a little higher than the national rate.

And the undocumented students surveyed had better GPAs than U.S. undergraduates as a whole.

The grades were self-reported, and the sample is not necessarily representative of all undocumented youth, Teranishi said. But, he added, it makes sense that undocumented students have higher GPAs than American undergraduates as a whole. Undocumented students often need scholarships or financial aid to attend college, and the bar for securing that funding is very high. Those who make it to college in the first place and then remain there, Teranishi said, are likely the highest-achieving students.

Indeed, the most significant factors in choosing a college for undocumented students were cost and location. The majority of the respondents—61 percent—reported that their household income was less than $30,000. Currently, 19 states offer in-state tuition or state grant aid to undocumented students attending public universities, while nine states restrict undocumented students from in-state tuition or prohibit them from enrolling altogether, according to the report.

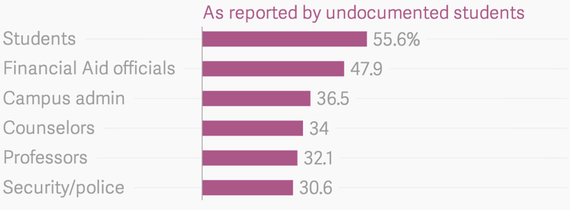

And the problems undocumented students face are not just financial and legal. More than half of the students surveyed said they had been mistreated by other students because of their legal status, and many also said they experienced negative or unfair treatment from college representatives.

That’s why programs like the one Rodriguez found at UC Berkeley are so key, the report’s authors say. Rodriguez (who wasn't a part of the study) is a peer academic counselor the Undocumented Student Program, where students are greeted with murals of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Cesar Chavez and a tree hanging with advice from generations of students.

There she offers other undocumented students both academic and emotional support. "Sometimes," Rodriguez says, "you just need somebody else who knows how you feel at that moment and knows exactly what you’re going through."