The most interesting news to come out of Nvidia's two-hour-plus press conference Sunday night was doubtlessly the Tegra 4 mobile processor, followed closely by its intriguing Project Shield tablet-turned-handheld game console. However, company CEO Jen-Hsun Huang also revealed a small morsel of news about the cloud gaming initiative that Nvidia talked up back in May: the Nvidia Grid, the company's own server designed specifically to serve as the back-end for cloud gaming services.

Thus far, virtualized and streaming game services have not set the world on fire. OnLive probably had the highest profile of any such service, and though it continues to live on, it has been defined more by its troubled financial history than its success.

We stopped by Nvidia's CES booth to get some additional insight into just how the Grid servers do their thing and how Nvidia is looking to overcome the technical drawbacks inherent to cloud gaming services.

What it is and how it works

The company's intent with Grid is to supply an entirely self-contained system that requires no extra hardware or software to do its job, so a rack of Grid servers actually has a couple of different building blocks.

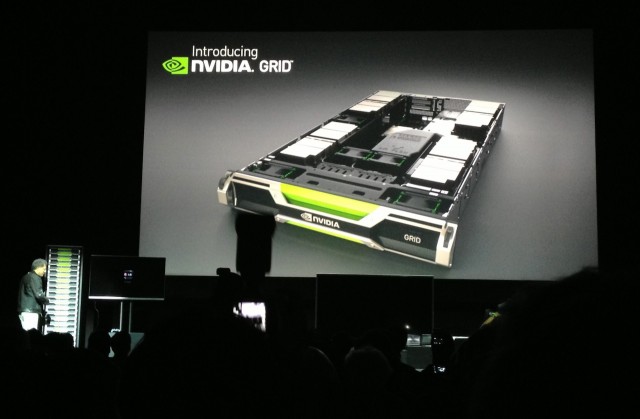

The main block of the Nvidia Grid system is the gaming server itself, a 2U rack-mountable box containing 12 Nvidia GPUs each capable of supporting two simultaneous users (for a total of 24 users per box.) To support more users, you simply add more boxes. These servers are likely using a variant of the same technology driving Nvidia's VGX graphics cards, which also promise cloud-based 3D graphics performance but focus on workstation applications rather than gaming. Each server rack (see above) can hold 20 of these servers, for a total of 480 users per rack, and each server consumes between 800 and 900 watts of power under load.

Coordinating the different Grid servers is handled by a separate "master" server, known as the management server. This handles things like user authentication, distribution of user sessions across servers, database storage for user credentials and information, and a few other things. Nvidia recommends that each 20-server Grid rack should be paired with one management server, which should balance the load effectively as well as provide redundancy.

Nvidia wants the process of running games on the Grid system to be as easy as possible for its partners and developers—as such, both the gaming servers and management servers are powered by Windows Server, so the games being streamed are just standard Windows PC games identical to the ones you'd play on your PC locally.

Battling lag

The biggest concern with any cloud gaming setup is latency, and Nvidia is bringing its experience in GPU-assisted computing to bear to reduce it, at least on the server end: the 720p and 1080p H.264 video streams that are sent to the user are actually encoded directly on the Grid server's GPU, rather than being sent to a separate server dedicated exclusively to the task of video encoding (and in so doing, increasing the likelihood of lag.) So how much faster is it than, say, OnLive's current system?

"[OnLive's] current implementation uses external hardware encoding, which takes a while," GeForce Grid product manager Andrew Fear told Ars. "When you're doing it like we're doing, on the GPU, it saves about 20ms of time for encoding over that. Also, through our drivers, we have a fast-pass recapturing encoding which saves another 10ms, so we can save about 30ms on the server. On the decode side, if we detect an Nvidia GPU, either a Tegra or a Geforce, we can use their decoder pack, which is also optimized, to save about 10 ms on the decode side. So overall we can save about 40 ms."

On the user's end, Nvidia says that users should only need about 6Mbps download speeds to enjoy smooth 720p video streams, a speed that should be well within reach for most cable and many DSL subscribers. When I asked whether the servers would support lower-quality or Netflix-style adaptive streaming to account for slower (or inconsistent) Internet connections, I didn't get a clear answer—the company is most interested in delivering clear 720p and 1080p video streams, even when playing on a small smartphone screen (just in case that small screen happens to be connected to a larger monitor or television). Whether the user can choose between 720p and 1080p streams (or other resolutions) will be left up to the service providers.

In theory, the service seems to work quite smoothly. Everything in the Grid section of the company's booth—a mix of smartphones, tablets, monitors, and televisions—was running off of one Grid server, which was delivering crisp lag-free images to everything. All of that said, there are still plenty of moving parts not present in Nvidia's booth—actual server load, large-scale implementations, and distance between the server and the user—that could all still make the service too laggy to be satisfying in the real world.

Convenience, not performance

To further improve the consistency of the service, the number of computing resources dedicated to each user is constant whether one user or 24 users are using the Grid server—this differs from many enterprise-class virtualization products, which can dynamically allocate CPU cycles or RAM or other resources to users based on server load.

The upside is that users should notice no differences in graphics quality or performance regardless of how many people are playing on a given server at a time. The downside is that graphical quality is fixed and generally won't exceed that of a mid-range gaming desktop—if you do the math from Nvidia's slide, 200 TFLOPS per rack divided by 240 GPUs divided by two users per GPU comes out to around 417 GFLOPS of performance per user, roughly equivalent to one of the weaker GeForce GT 640 cards according to this handy table (or nearly twice the raw graphics performance of an Xbox 360, a common comparison point for graphics performance throughout CES). Nvidia still wants to sell its GeForce cards, after all, so gamers who want the best visuals are still going to be pushed in that direction.

The Grid server system (and the services that are powered by it) are intended, rather, to bring PC gaming to places where it couldn't otherwise go: namely smartphones, tablets, and low-end PCs. Nvidia's own Grid demo during the keynote was run on an Android tablet tethered to a Bluetooth gamepad. Nvidia also wants to have clients available for even more devices, including smart TVs and set-top boxes—anything that can decode an H.264 stream and connect to an input device can, theoretically, become a gaming PC.

Content is still king

It's worth noting that all Nvidia is doing with the Grid is providing the backend for a cloud gaming service—it will be up to partners to purchase the servers, build services, and then convince developers and publishers to make their games available on those services. That more than anything has been the biggest drawback of cloud gaming services so far: they simply can't compete with what's available on the virtual store shelves of an established store like Steam. A few partners—Agawi, CloudUnion, Cyber Cloud, G-Cluster, Playcast, and Ubitus—were announced at the keynote on Sunday, but only Agawi is based in the United States and none of them are large.

Nvidia is selling dev kits comprised of one management server and two gaming servers to its partners now at an undisclosed price, and this is where the technology will ether flourish or languish. Nvidia envisions cloud gaming services that are as affordable, reliable, and widely-used as Netflix is today; all they need to do it is buy-in from the people who actually make games.

Additional reporting provided by Kyle Orland.

Listing image by Andrew Cunningham

reader comments

81